EVs present new but surmountable challenges to first responders

By KATE COIL

TML Communications Specialist

As electric vehicles become more common on roadways, both emergency responders and motorists are asking questions about how fighting EV-related fires or handling EV-related accidents differ from those involving the traditional combustion engine.

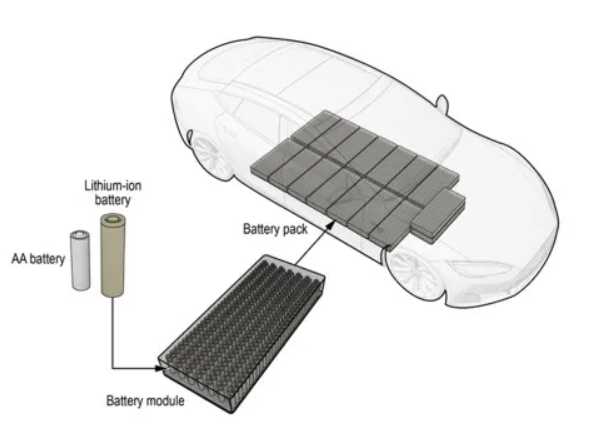

Data from the National Traffic Safety Board (NTSB) showed that EVs are involved in fire situations at a lower rate than both their internal combustion engine (ICE) and hybrid counterparts, but the risk of reignition of a fire is higher in an EV and are different than in ICEs. While fuel and wiring are more likely to cause fire issues in gas vehicles, battery issues are the more common cause for fires in EVs and hybrids.

NTSB has issued several safety recommendations for emergency responders when responding to electric vehicle fires where high-voltage lithium-ion batteries are involved in particular. The NTSB has investigated several incidents where fires were caused by these batteries being involved in high-speed crashes and noted that in these situations, the batteries have the tendency to reignite.

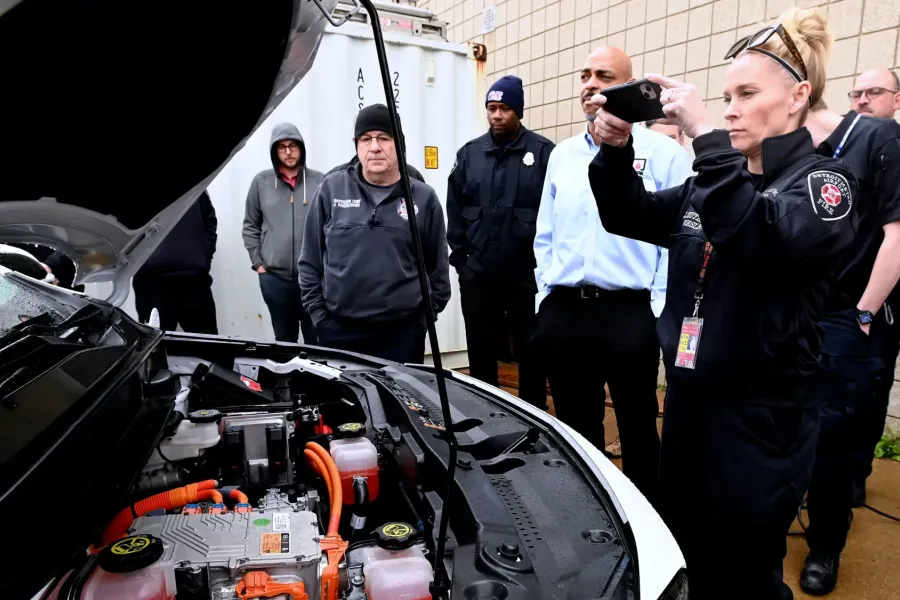

With Tennessee becoming a hub of EV manufacturing, fire officials across the state are already exploring ways to make first responders have the tools and technology they need to address fire-related issues.

Donald Pannell, a fire management consultant with UT-MTAS, said each department develops their own Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) based on the risks in their community and their operational capacity, and while not all departments may have specific SOPs for EV fires, it is easy to develop them.

“Though EVs are still relatively new, though growing at a rapid pace, responses to vehicle fires are not new, and existing

SOPs, that may have been primarily based on anticipated responses to ICE vehicles, are often adaptable to a level that can allow their successful application to any type of vehicle fire,” Pannell said. “Regardless of the vehicle powertrain, tactics used in a vehicle fire incident action plan should consider several common components. First, a proper incident size up should be performed to identify the scope of the incident, scene safety needs for first responders and patients/victims, the number and type of vehicles involved, extrication and emergency medical treatment needs, and determine the best tactics based on response capabilities. The tactics that are developed will be based on several factors including the availability of a sustainable water source as EV fires can require much more water than an equivalent ICE vehicle fire. Other factors include the availability of sufficient fire/emergency medical personnel and apparatus/equipment.”

Jason Sparks is the fire program director with the Tennessee Fire Service and Codes Enforcement Academy (TFACA), which is part of the State Fire Marshal’s Office. Sparks said time, water, equipment and resource needs, and knowledge of how EVs operate are the biggest things departments need to consider when tackling an EV fire.

“There are some new challenges with EV fires that will affect the fire services response to these types of calls,” Sparks said. “From the amount of time units are committed to the emergency, fire stream application, water supplies, additional equipment and resource needs and knowing where the batteries are located on the EV. Time must be committed to this emergency. This is based on the amount of time it takes to extinguish the fire and cool the batteries of the EV. The goal is to cool the batteries to the ambient temperature. Once that has been accomplished, the vehicle should be monitored for 45 minutes to ensure we do not have reignition of the batteries. “

Both Sparks and Pannell agree that water is still the best extinguishing agent for EV fires, Sparks said this method still includes some challenges.

“The difference is how the water is supplied to the fire,” Sparks said. “Like most vehicle fires, we will knock down any visible fire, then we will concentrate our efforts on the vehicles’ batteries. The goal here is to apply water directly to the batteries themselves. This is where knowing the location of the vehicle’s batteries is important. Also, the amount of water needed to accomplish this task can be a minimum 4,000 gallons and we have had reports of more than 14,000 gallons. The best way to apply the water needed to cool the battery of an EV with a floor pan battery is to lift the vehicle. This exposes the underside closest to the battery and apply the water directly onto the location of the batteries. In some cases, most engine companies may not have the required equipment needed to lift the vehicle safely. This could require the request of additional resources to perform this task. By drilling this down, we find that the effects it will have on the fire service include longer on scene times, large amounts of water and the challenges to provide it along with more resources and equipment.”

Most considerations for EV fires occur due to accidents on open roadways, but there are also occasional reports of EV fires taking places in garages in residences or public parking facilities. Pannell said handling an EV fire may require different strategies in more enclosed spaces.

"This is certainly one of the big issues,” Pannell said. “If an EV fire is in the open, exposures are often limited. However, a sustainable water supply may not be readily available – think about a vehicle fire on an interstate highway where there are no fire hydrants. If the EV fire is inside a structure, the potential for the fire to extend beyond the area of origin is a real possibility that warrants additional tactical planning and actions. This type of incident can quickly change from a vehicle fire response to a structure fire response bringing with it all the complexities of that type of call.”

New tools and technologies are already coming on the market aimed at helping firefighters and other emergency responders more effectively deal with EV battery fires. Sparks said the state fire marshal’s office is working to keep departments updated on whether or not these new tools will be of more benefit them than traditional methods.

“At this time, we have found that most all fire departments that are recognized by the state fire marshal’s office should have access to the equipment needed to deal with an EV fire, but we are already seeing equipment manufacturers pushing out new tools that could assist in fire extinguishment of EV,” he said. “Only time and research will tell if using the new tools will be more effective and safer for responders.”

Pannell said departments may want to decide for themselves if they want to invest in new tools and technology, but they may find the tools they already have can help in these situations.

“Certainly, continued and regular training on policies and with practical scenarios related to these emerging technologies should be conducted,” he said. “The typical cache of fire suppression and rescue/extrication tools are needed. Additionally, thermal imaging cameras, fire suppression lines with in-line foam capability, and piercing nozzles have proven useful to fire departments for responses to these incidents. Using a thermal imaging camera can help with an effective 360 size-up. Additionally, other SOPs such as establishing an appropriate command structure, the use of appropriate PPE/SCBA, protecting the work area, stabilizing the vehicle, performing patient care and extrication, and control and clean-up of run-off should be followed.”

Education is still the best tool when it comes for tackling any fire situation.

“Other areas that we have identified for EV response include the infrastructure that supports the charging of the vehicles and vehicle crashes,” Sparks said. “This includes both residential and commercial application for charging the vehicles. Our goal is to educate responders to identify the hazards that could be found and how to safely mitigate them. As for vehicle crashes, the research shows that by understanding the anatomy of the vehicle and how to isolate the batteries energy and deenergizing the high voltage components, we can use the same technique in EV as in other vehicles to perform patient rescue.”

By understanding the challenges EVs present, Pannell said departments can better ensure the safety of their first responders.

“Another concern that departments should consider when dealing with EV fires related to car wrecks is the risks of electric shock and battery reignition that can arise from the stranded energy that remains in a damaged battery and high-voltage system,” Panell said. “A current guiding ‘rule’ related to incidents involving EVs is to always assume the high-voltage battery and associated components are energized and fully charged. Damaged cells in the battery can experience thermal runaway – uncontrolled increases in temperature and pressure – which can lead to battery reignition. EV fires have a significant chance for re-ignition hours after extinguishment. Many experts have said re-ignition should be expected.

At present, all firefighters that meet NFPA 1001 standards are capable of responding to EV fires. As more technology and information emerges, however, both Pannell and Sparks said there may be different or more specialized education focused on this topic. Officials with the Tennessee Fire and Codes Academy are one major resource Tennessee fire departments can rely on for education on this subject. Other resources are available from organizations like the NFPA, the International Association of Fire Chiefs, the International Association of Fire Fighters, the U. S. Department of Transportation’s National Traffic Safety Administration, and the U.S. Fire Administration among others.

Additionally, departments can take their knowledge and share it with the public so motorists are better educated themselves on what to do in an EV fire situation.

"The subject of EVs provides another opportunity for fire departments to engage with members of their communities to educate them on risks and related preventative measures to improve fire and life safety within the communities,” Pannell said. “The same partners listed above, among others, also provide a variety of public facing educational materials, and many of them are free for fire departments to use as-is or to customize.”