Radar survey shines new light on historic Gallatin City Cemetery

By KATE COIL

TT&C Assistant Editor

A walk through Gallatin’s historic city cemetery is a walk through the city’s history.

Ken Thomson, president of the Sumner County Historical Society, said the first plot of land on which the cemetery was built was donated by former Gallatin resident and Tennessee politician Felix Grundy and has expanded several times since. Established in 1814, the Gallatin City Cemetery has more than 8,000 interments and was long considered the place for prominent residents of both Gallatin and Sumner County to be buried since its first interment in 1818.

Markers in the cemetery show the graves of early settlers, two former U.S. Congressmen, Tennessee Gov. William Trousdale, Tennessee First Lady Eliza Allen Houston Douglas, and monuments and tombstones honoring veterans of wars including the Civil War, Mexican American War, World War II, World War II, and Vietnam.

However, it was more than 500 individuals without markers highlighting their final resting places who were recently honored by city officials and Gallatin residents. At the time of the cemetery’s establishment, Gallatin’s cemetery was segregated and black residents – many of whom had at one point been enslaved – were buried in the back of the property, often without markers.

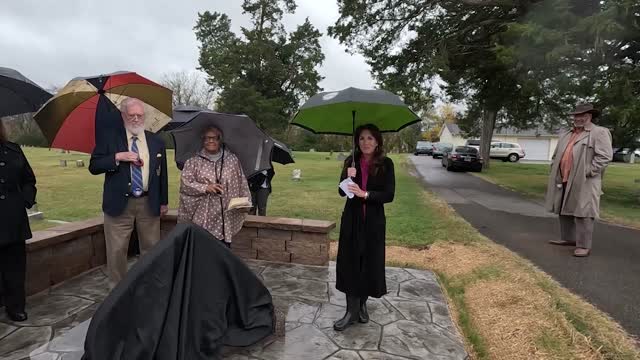

Now, a permanent marker has been erected by the city to honor those buried in this section and celebrate their contributions to Gallatin. At the dedication ceremony, Gallatin Mayor Paige Brown described the project as “significant and meaningful” to the entire city.

“So many people don’t realize that the empty space here is very significant to the history of Gallatin,” she said. “The idea was created over time with a lot of creative and smart people to find an appropriate way to commemorate the people who are buried on this ground that don’t have individual markers... This speaks volumes about who we are as residents of Gallatin. It’s so much more than a grave site, and we’re really just getting started in what can be done out there.”

The project began several years ago with the creation of the Friends of the Gallatin City Cemetery, a committee intended to both preserve the cemetery’s landscape and its history. Retired educator and local historian Velma Brinkley said one of the issues the board faced was that space was running out at the city cemetery. The city received a $15,000 donation from Volunteer State Bank to see how many spaces were still available.

“There was a section of the cemetery that appeared to be empty, but no one knew for certain if it was,” Brinkley said. “There were some who thought it was half empty and others who thought it was partially full. When the city was given these funds to hire someone to come in and conduct a study to find out how many graves where in the area and how much of the space had been utilized, that was when we learned – to our amazement – there were more than 500 graves.”

Matthew Turner, vice president of Virginia-based GeoModel, mapped both marked and unmapped graves at the Gallatin City Cemetery in 2018 using ground penetrating radar (GPR). At the time, Turner said he had performed GPR mapping for a number of cemeteries, both public and private.

The GPR process sends radar waves into the ground the time and way in which they respond back to the machine can be used to indicate not only if something is below the surface but also the likelihood of if what is underground is concrete, asphalt, masonry, cables, pipes, metal, fresh water, structures, or event human remains. Ground penetrating radar is used in a variety of applications including studying bedrock, for environmental remediation, in archaeology, for engineering testing, detecting landmines, locating underground utilities, and mining.

Thomson said there were once records indicating burial locations in the cemetery, but a fire in the 1950s destroyed most of them. The mapping of the back section at least gives both historians and officials overseeing the cemetery a map of where there are burials.

“We have a burial book from the 1850s to the 1880s that gives some information,” Thomson said. “I have checked the list of tombstones we have against that book, and about 50% of those people have no marker today. It is not unusual to not have markers. We know certain people were buried there or had a lot, but if they don’t have a marker, we can’t find it.”

Brinkley said some of the burials may have once had temporary markers that have long since dis

appeared.

“We know they sometimes used field stones, because down through the years in maintaining the property, these field stones gradually disappeared,” she said. “It is hard to cut around a field stone to keep the land looking pretty.”

Thomson estimated 50% of the people buried in the cemetery are in unmarked graves, and many of those graves in the largely unmarked section may have been freed African Americans living prior to the Civil War as well as the formerly enslaved and other members of the African-American community who were buried there following emancipation. Thomson said those living in slavery were often buried on the property of their enslavers, but it also isn’t uncommon for cemeteries to have large sections of unmarked graves, often known as “Potter’s Fields,” that were set aside as burial sites for poor and non-white residents.

Since the dedication, Brinkley said not all of those buried in the cemetery have proved to be completely anonymous. At least three people have thanked her for her involvement in the project and mentioned that they have relatives buried in unmarked graves in the cemetery.

Other important historical figures buried somewhere in the section including several of the Gallatin area businessmen who launched Gallatin’s African-American Fair. Founded soon after the conclusion of the Civil War, this fair served as an important economic and cultural event for the black community in Gallatin until its last season in 1977. Following the Great Migration, it also served as an important homecoming event for Gallatin natives.

Fair founders Mack Randolph, Arthur Banks, Willie Baker, Dock Blythe, John Banks and Henry Ward created the event after being recently emancipated and also became business leaders in the community. Brinkley said she is discussing having their story portrayed as part of an annual October tour of the Gallatin City Cemetery that highlights the lives of past residents.

From a historical perspective, Thomson said the experience has added more pieces to the puzzle of Gallatin’s past.

“People need to know that these people are there and each one of them donated something to the society we live in,” he said. “They were all part of the life of this community. History needs to be documented, no matter if it’s a cemetery, structures, or people. We would have nothing if we did not have records.”

Brinkley sees the monument as a way for Gallatin to honor its past as well as put into practice its current values.

“I think that as a civilized people that we owe that much to our ancestors, regardless of what color, race, ethnicity, or whatever they were,” she said. “We owe that degree of respect to those who have passed on. They deserve our respect, and I feel we should acknowledge that we know they are there. We may not know your name, but we recognize you as having been loved, as having lived and worked here. We know you were here, and you made a difference.”

Thomson said she hopes the entire project encourages Gallatin residents to reflect on the history of their city.

“I think it’s a wonderful thing and long overdue to honor those sainted people,” Thomson said. “The city cemetery contains the history of Gallatin, and it’s up to us to preserve that history. Life is a voyage of exploration and discovery, and we definitely discovered 500 people who were part of a long chain of lives, each contributing to our community. They are among many who pioneered a new life of freedom with the ending of enslavement. We need to show our appreciation to those people, even if we don’t know who they are.”

Brinkley also encourages other city leaders to look into seemingly vacant sections of their own city cemeteries as there may be more to the hallowed ground than meets the eye.

“Typically, of that time and period in history, African Americans were buried at the very back and typically in a back corner of public cemeteries,” she said. “If you have a space in the back of your cemetery that appears to be unused, the chances are very great it houses burials for ex-slaves, depending on the age of your cemetery. There may also be the remains of those who could not afford a headstone and were buried with a simple field stone or marker denoting their location. As soon as the person who put that stone passed away, all knowledge of that stone and its meaning was gone. The chances are very great that if you space in the back of your cemetery or in a certain corner furthest from the entrance, more than likely you have burials of African Americans.”

Brinkley said the project shows how Gallatin is still living up to its reputation as being the Nicest City in America by Readers’ Digest in 2017.

“I was thrilled my city wanted to do this memorial, but I was not surprised,” she said. “That is the kind of city Gallatin is. God created us all, and we are all equal in his sight. Given that we are the Nicest City in America, this is what I really expect of my city. There are so many people who think as I do about showing respect for self and others. Gallatin rose to the occasion again.”