Municipal workers, essential employees faces of affordable housing crunch

By KATE COIL

TML Communications Specialist

With housing prices hitting record highs across the country, officials are hoping to reframe the conversation about what affordable housing is and who needs it.

The Tennessee Affordable Housing Coalition (TAHC) is a membership organization that works to advocate, educate, and connect resources across the state of Tennessee to drive the availability of affordable housing. Anyone can be a member of the group, which includes bankers, realtors, government officials, private citizens, non-profits, and others.

Dominique Anderson, TAHC executive director, said the pandemic exacerbated what was already a growing issue, not just in Tennessee but across the country.

“The affordability issue has been a conversation for quite a while,” she said. “It started more about a lack of access information and knowledge about how to purchase a home and credit misconceptions. Fast forwarding to the pandemic, you have joblessness, fear, and people wanting to move out of city centers. You have people who can’t make their mortgage or rent after moratoriums ended. The pandemic really put a spotlight on an issue we were already having.”

Anderson said all areas of the state face affordable housing issues but the specific issues themselves vary from place to place.

“We know everything is a little different across each region of the state,” she said. “East Tennessee is driven by an aging population that have homes that need upkeep and repair so people can age in place. With Nashville being an ‘it’ city and cities around it becoming part of that, housing stock is a major issue in Middle Tennessee – as it is in much of the country. That means housing can’t be built fast enough, and this is coupled with an influx of investors who are coming from out of state buying properties unseen. For West Tennessee, the prices of housing are rising and not meeting the wages. This is also part of a national and international problem where wages aren’t rising to meet the cost of housing.”

In addition to regional issues, Anderson said there is also often an urban versus rural difference when it comes to affordable housing needs.

“East Tennessee is much more rural than Middle Tennessee and West Tennessee just by area,” Anderson said. “We have also had generations of people living in the core of cities like Nashville or Memphis. As people want to buy up as much property in the core, those areas become negatively gentrified, and there is a fair amount of displacement.”

Angela Hubbard, director of housing with the Metro Nashville Planning Department, said there are still some commonalities all areas of the state share when it comes to housing issues.

“At a very basic level it’s a supply and demand issue,” she said. “When you have the population growth across the state – not just in Nashville – and then you have people coming into a city or a county that have incomes that make them cash buyers, who can outbid on a home or purchase or afford the rents, it drives it up. We also have investor buying, which I hope has peaked. Nashville is no different than other cities. We are not only dealing with affordability issues but also equity issues, which are historical discriminatory practices in the housing industry. While housing has been a growing issue, the response has really been recent.”

Both Anderson and Hubbard said part of the problem is most people don’t realize who is really seeking affordable housing.

“NIMBY-ism – not in my back yard – needs to be addressed,” Anderson said. “We are rolling out a campaign that is showing the true faces of affordable housing. Understand your daughter may have graduated with loan debt, may not be able to afford housing, and has to move back with you. That burdens you and your family. That is a face of affordable housing. Your favorite nurse at your doctor’s office may be late for work because she lives further out, her child goes to school where they live, and she has to drive him to school and then go to work.”

Hubbard said many do not realize those faces of affordable housing include many government employees.

“It’s very stigmatizing to our neighbors, and our people who keep our cities and counties running,” she said. “This includes our firefighters, our police, our healthcare workers from the front desk to nurses, teachers, teachers’ aides, administrative staff, and everyone in that whole income spectrum. Housing has been treated as a commodity, and commodities are easy to dehumanize. We have to talk about the humanity about housing, and it’s really about housing and health. Housing leads to better health outcomes, better educational outcomes, and better job performance. The not-in-my-back yard challenge to me is one of the biggest challenges. Even if I had the funds to build all 5,000 units we need per year in Nashville to meet our growth, I wouldn’t be able to find a place to put them because people say not in my neighborhood.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines any household (family of four) making 80% of an area’s median income (AMI) as low-income, and this number typically includes 40% of the area’s general population. For example, the state of Tennessee’s AMI for a family of four is $54,833 per year, meaning a low-income family is any family of four making at the most $43,867 per year. Of course, HUD data is not calculated statewide but based on data from the U.S. Census. Nashville’s median income is based on census data drawn from the Greater Nashville census tract that also includes Franklin and Murfreesboro.

As a result, Hubbard said wealthier areas of the census tract can skew the “average income” for the entire 10-county region in Nashville’s metropolitan statistical area and puts the area’s average income at $94,899 per year for a family of four. According to 2021 data from HUD, a family of four making at the most $67,450 per year — or an individual making $47,250 — is considered 80% of the median income in this region and is in the target group for “affordable housing.” As of May 2022, the average house price in the Greater Nashville area was $470,000.

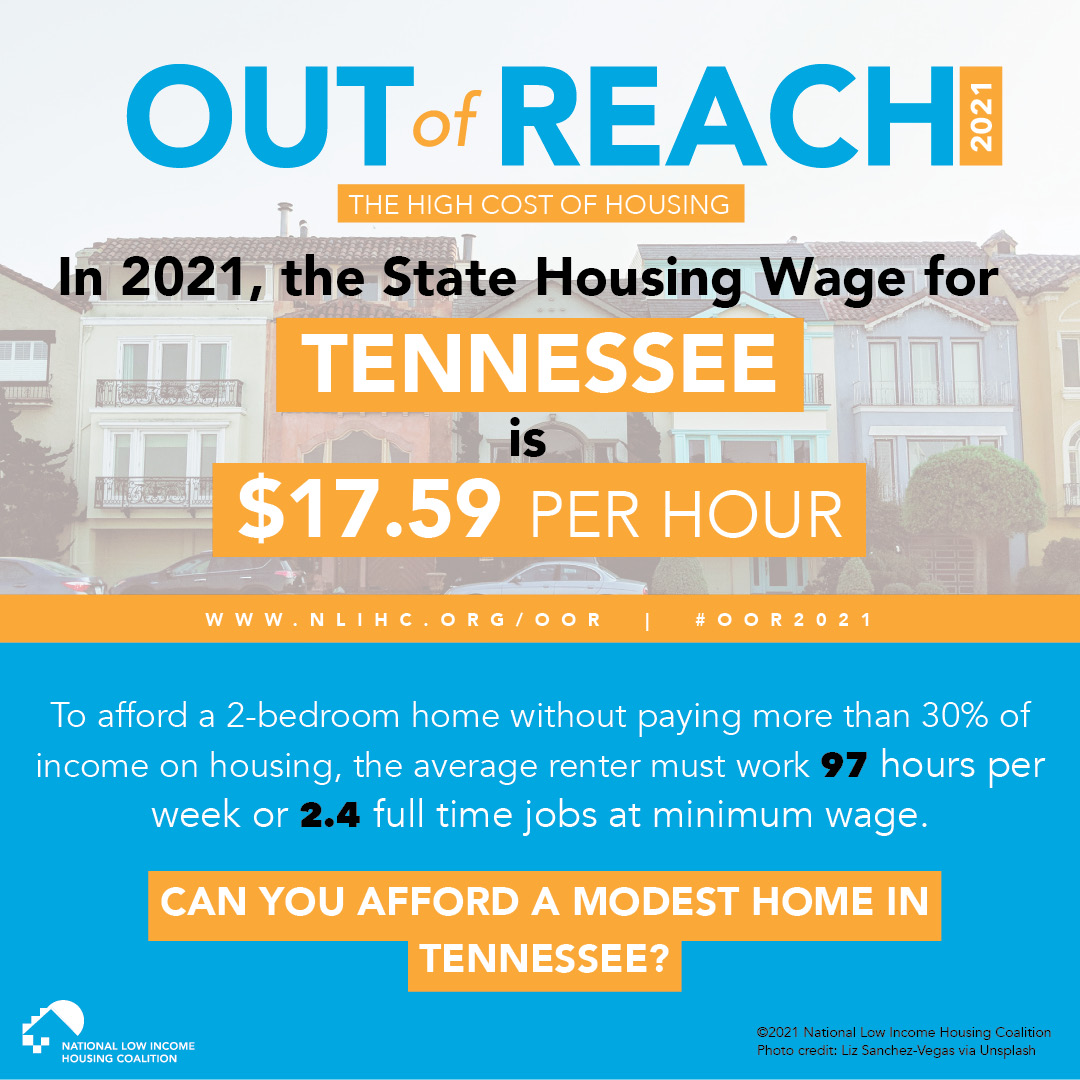

“When we talk about affordable housing, it is actually defined in state law as people with incomes at or below 80% of the median income,” Hubbard said. “Workforce housing is for those at 60-120% below, but I don’t like either of those definitions or terms because workforce housing implies people in affordable housing aren’t working. Actually, they are working poor and many of them have three jobs. Nashville’s rents in downtown are $1,000 more than what is called the fair market rents HUD calculates. There is no one at even the area median income that can afford to rent in downtown Nashville. Really, affordability means any of us shouldn’t be paying more than 30% of our income on housing costs. As the income scales down, the more pressure it puts on a family to afford their rent.”

Anderson said many programs in place that specifically target helping house these essential employees are underfunded and cannot work fast enough to bridge the gap between stagnant wages and rising costs.

“Funds for teachers, EMTs, police, and other public servants were created across the country to spur local homeownership, but the problem is that those funds dry up quickly and the ‘pots of money’ are underfunded, as well,” she said. “Of course, the other key issue is that wages for these key workers are not keeping up with the price of housing. So, no matter what type of DPA programs exist, if that buyer is going to be ‘house poor’ another problem is created. An ideal situation would be that municipalities would work with for-profit and non-profit developers, as well as their local blight programs, land banks, and other groups to create an ecosystem of rehabbed, renovated properties provided for little or no cost to the developers/rehabber incentivizing renewal of current home stock that can be updated and made available at a reasonable rate.”

From a municipal perspective, Hubbard said a lack of affordable housing could mean losing out on employees in vital services and industries who have to live and work somewhere they can afford.

“It impacts the running of our city and the functions that we all rely on,” she said. “We want to have a city that has a great quality of life for everyone, and when that starts unraveling because we aren’t creating that opportunity, it’s not just people being individually impacted by their housing situation. It’s everyone whose lives are so intertwined with fire protection, police, and the service industry. We rely on tourism dollars for so many things and businesses rely on tourists to come. When service is slow at a restaurant or hotel rooms can’t get clean because the people who work those jobs aren’t making a living wage, that impacts our overall economy. We have to talk about the economics of housing.”

There is also a lack of public understanding about how some tools like zoning can be used to address housing issues

“The word densities is a term that scares people” Hubbard said. “They think it automatically means a 14-story high rise, but really in smaller places it can be activating the second story of a downtown storefront on Main Street for housing. We lack real planning around housing at all levels. Even in Nashville, we are working to get the right data. We know at a macro level the need, but what we are working on is determining what we have built out and how do we make families who need access to that housing know what is out there. That granular level is what we really have to focus on now.”

Anderson said housing is at the center of many other issues cities face. By addressing housing, statistics show communities also end up addressing issues including public transportation, education, public safety, health and wellness, and more. Those who own homes are more likely to have stability at work and at school and are more likely to raise children who will own homes.

“Housing is really a cycle,” she said. “Homeownership really does provide a great asset, especially for families and low-income earners. Affordable and stable housing creates a difference in our education system. A happy, healthy child with a place to lay their head that is clean and safe does better at school. As they do better at school, they become more productive themselves and can then buy a home as an adult.”

Hubbard said Nashville began looking at housing issues under the administration of former Mayor Bill Purcell in the early 2000s, at which time the only tool the city had to address affordability issues was the Home Investment Partnerships Program. That federal program remains the only program the city has available to specifically build affordable housing on its own. Tax-Increment Financing (TIFs) were used to encourage affordable housing development in downtown development prior to the Great Recession, but Hubbard said it wasn’t until the city created the Barnes Fund a decade ago that new opportunities opened up.

However, Hubbard said one issue Nashville and other cities are facing when it comes to helping address affordability issues is that some tools available in other places are not there in Tennessee. She said citizens often do not understand the limitations cities face.

“People ask us if we can do something about rents rising,” Hubbard said. “We can’t. There is a rent control law in Tennessee that prevents us from controlling rents from increasing. Outside of having any federal, state, or local subsidy or resource or incentive, we can’t control increasing rent prices or increasing sales prices. The other thing we can’t do is require affordability as part of any rezoning, which is also a statewide thing. We do not have any regulatory tools to address affordability, so it has to come through voluntary incentives that require resource allocation at the local level. That is a really hard conversation for people to have, because that cuts into resources for schools, roads, and public safety. It is really important to see where we can’t act, which determines how we have to act.”