CIT training produces positive outcomes for first responders, citizens, and families

By KATE COIL

TML Communications Specialist

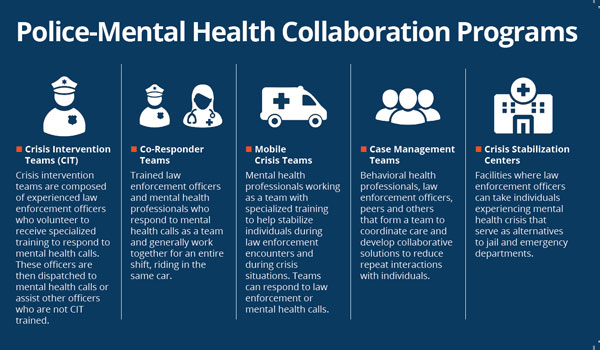

To ensure engagement with individuals experiencing mental health crises have positive outcomes, more law enforcement agencies and first responder units are taking advantage of crisis intervention team (CIT) training.

Overall, 43.8 million adults in the U.S. experience some type of mental illness every year with nearly 10 million Americans struggling with serious or ongoing mental health issues – numbers exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent survey of law enforcement agencies found that approximately 15% of all emergency calls are related to a mental health incident. Nearly a quarter of all individuals killed in officer-involved incidents are having a mental crisis at the time and those with mental health issues are 16 times more likely to be killed than any other type of suspect profile.

Following a series of nationally publicized incidents where interactions between mentally-ill individuals and law enforcement officers produced negative results, more and more agencies are trying to ensure their officers are trained to deal with these situations and produce a good outcome for everyone involved.

CIT training has its origins in Tennessee with the “Memphis Model,” which was created through a partnership with officers with the Memphis Police Department, the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS), the Tennessee Department of Correction, and Tennessee’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI-TN).

Kim Rush King, crime intervention team director with the National Alliance on Mental Health’s (NAMI) Tennessee chapter, said the goal of CIT training is to bring various resources and community agencies together to support police work.

“It really started because between 1986 and 1987 there were four major incidents between the Memphis Police Department and people who were mentally ill that did not end well,” Rush King said. “After the very last incident in 1987, NAMI-TN’s Memphis affiliate went to the Memphis Police Department and said I think everyone has realized this isn’t the fault of law enforcement because law enforcement has never been trained to handle someone in a mental health crisis.”

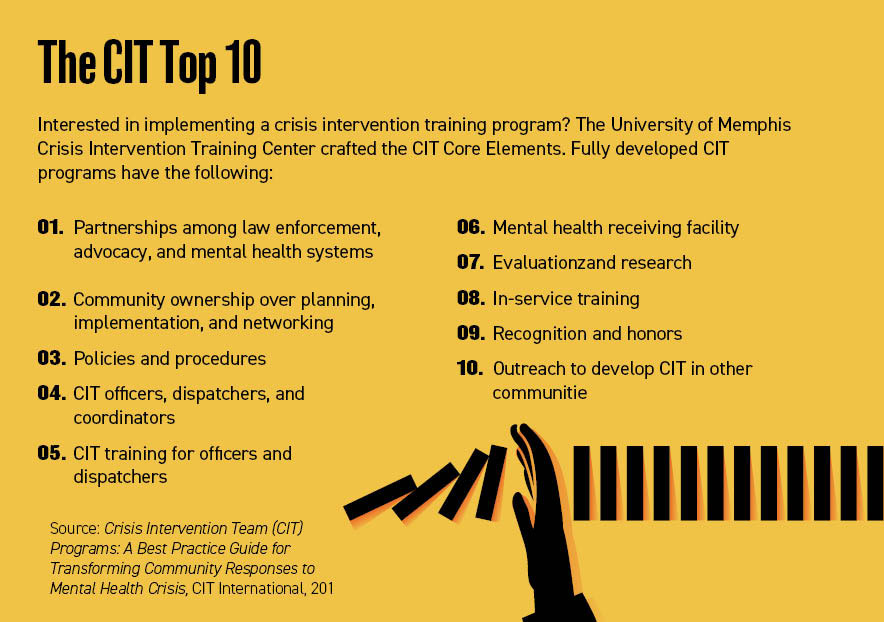

Memphis Police Maj. Sam Cochran, since retired, and University of Memphis psychology professor Dr. Randy Dupont worked together with various community agencies and organizations to create the “Memphis Model” that provides 40-hours of free, P.O.S.T.-certified training for law enforcement officers on how to improve outcomes during encounters with people living with behavioral health challenges. The model was first established in 1998, and has since spread across the country. Dupont still serves as the director of the Memphis Police Department's and Memphis Fire Department Critical Incident Services.

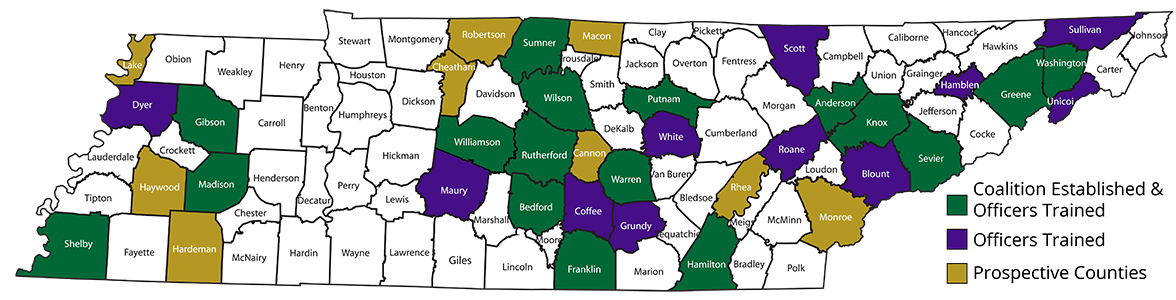

Lisa Ragan, director of consumer affairs and peer recovery services for the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TNDMHSAS), said further investment in the CIT model came for Tennessee in 2017 when the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) gave the state a planning grant aimed at expanding CIT training through work with NAMI-TN.

“That helped revitalize CIT throughout the state,” Ragan said. “It led to the development of a CIT Task Force on how we could support local communities across the state to adopt the process. Since then, we have received another DOJ grant with NAMI-TN and the department has also added significant funding to support the program.”

While many departments are interested in adding CIT training or professionals to their staff, Rush King said not all officials know what to expect when it comes to the program.

“CIT really is all about community partnerships,” she said. “In talking with law enforcement officers across the state, when it comes to dealing with a person in a mental health crisis they really don’t know where to go. They don’t know where their resources are in the community. Usually, the person ends up in either jail or the hospital. We bring community partners and resources together and educate departments. We develop steering committees for these community partners that meet once a month."

The other part of the training is the 40-hour, week-long training program for officers, which is offered at no cost to any department that wants it.

“A lot of the focus on it is on mental health,” Rush King said. “Mental health is a large umbrella, so topics under that might be someone who has dementia but it looks like a psychotic episode. You need to deal with that person differently than a veteran who is dealing from a flashback with PTSD. We do a special hour and a half on autism.”

Medications and their effects are also discussed during the training sessions as well as how to recognize the signs of a person who may be self-medicating with non-prescription means.

“We also get pharmacists and nurse practitioners in to talk about what medications these people might be on,” Rush King said. “We might encounter people who are having issues because they don’t want to take their medications because of the side effects, so we educate them on what the side effects are and why there is such a cocktail meds for some conditions. Because law enforcement deal with a lot of illegal substances, we also discuss how a lot of people may have a primary mental health diagnosis with a secondary substance abuse issue. It gives them a way to step back a little bit and explore more of the issue.”

Training also brings in those with mental health issues and their family members to discuss their dealings with law enforcement.

“Hearing it from their perspective really resonates with the officers,” Rush King said. “We then get into the de-escalation model and role play based on real calls. At the end of the training, we have a graduation ceremony and each county has designed its own pin for officers to wear. When someone with mental health issues sees an officer with that pin, they know they are with someone who has been trained to help them.”

Rush King said she has noticed in uptick in the number of agencies seeking out CIT training, especially in rural communities. NAMI-TN held nine trainings averaging around 25-27 officers between August and December 2021 with even more scheduled for this year.

“CIT spreads by word of mouth,” she said. “The sheriff of one county will talk to the sheriff of another county next to them. I am getting more calls and emails asking about CIT. That’s the beauty of it. I’m especially interested in helping our rural counties in Tennessee.”

NAMI-TN has also utilized DOJ funds and a partnership with the Hendersonville Police Department to given data-driven examples of CIT success.

“Through our DOJ grant, we have also established a small data form that collects data,” Rush King said. “The Hendersonville Police Department has agreed to do a pilot with us using that form. Now, we are able to track more of the mental health calls that come in. When we dispatch a CIT officer to that call, we are seeing fewer and fewer arrests because those issues are being handled elsewhere. Because of CIT and the training that officers and first responders have received, they are able to recognize symptoms of certain diagnoses as well as ask questions they’ve never thought of asking before. By keeping that conversation going, you are able to de-escalate the situation and find better solutions.”

Rush King said she frequently gets texts or emails not only from officers about how CIT has improved their policing but also from those with mental health issues and their families expressing how CIT-trained officers made a difference in their lives.

“I was forwarded a Facebook post from someone in the Upper Cumberland area that was talking about the CIT officer who responded to her and how kind and helpful they were to her,” she said. “I forwarded that information on to the police chief. It’s hard enough for a person or their family to experience a mental health crisis. It’s important to know that when they call law enforcement that their loved one is going to be taken care of, that those officers know and understand because they are trained. Honestly, all of us need to see that somebody cares.”

Ragan said knowing local officers are trained in CIT can be reassuring for members of the public.

“It’s incredibly comforting and reassuring to feel like you can turn to the police in a crisis situation and you are going to get someone who is trained appropriately. It is a best-case scenario for someone’s loved ones. That’s kind of the beauty of the community coalition and local CIT groups that meet regularly. That can include individuals with lived experiences, family members, and others who can play an active role, making connections and building community.”

CIT training can make a major difference for officers as well.

“CIT does not take the place of officer safety,” she said. “It’s all about patience, slowing down, and taking the time. The benefit is they learn what resources are available, which is the most amazing thing for many officers. It gives them options they didn’t know they had before. It also reduces arrests and use of force.”

While keeping those with mental health issues from incarceration can save tax dollars, Ragan said the most important result from CIT is that it ensures both officers and individuals in crisis go home at the end of the day.

“It absolutely saves lives,” Ragan. “It is a proven method. It’s a win-win for everyone. People are going to get the care they really need. They are going to be diverted from incarceration whenever possible. It really improves job satisfaction for the officers themselves. They want to help people, and this gives them the tools to help people in a positive way. It improves community relationships and the community itself.”

To learn more about CIT training, visit https://www.namitn.org/ or https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/cit.