Homebuilders highlight how municipal leaders can address housing issues amid unprecedented growth

By KATE COIL

TML Communications Specialist

As home prices skyrocket across the country, Tennessee homebuilders want to educate government officials on the issues they face to keep new homes affordable, especially as the state expects an influx of new residents to meet growing industry needs.

With an estimated 5,800 people expected to be employed at Blue Oval City alone – not counting the estimated 21,300 employees automotive suppliers and other support services will bring to both the region and across the state of Tennessee – West Tennessee is expected to see an explosion in population. The challenges of meeting the residential needs these new jobs will create as well as the realities homebuilders face in the present market was the topic of a Blue Oval Community Impact meeting hosted by the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development (TNECD).

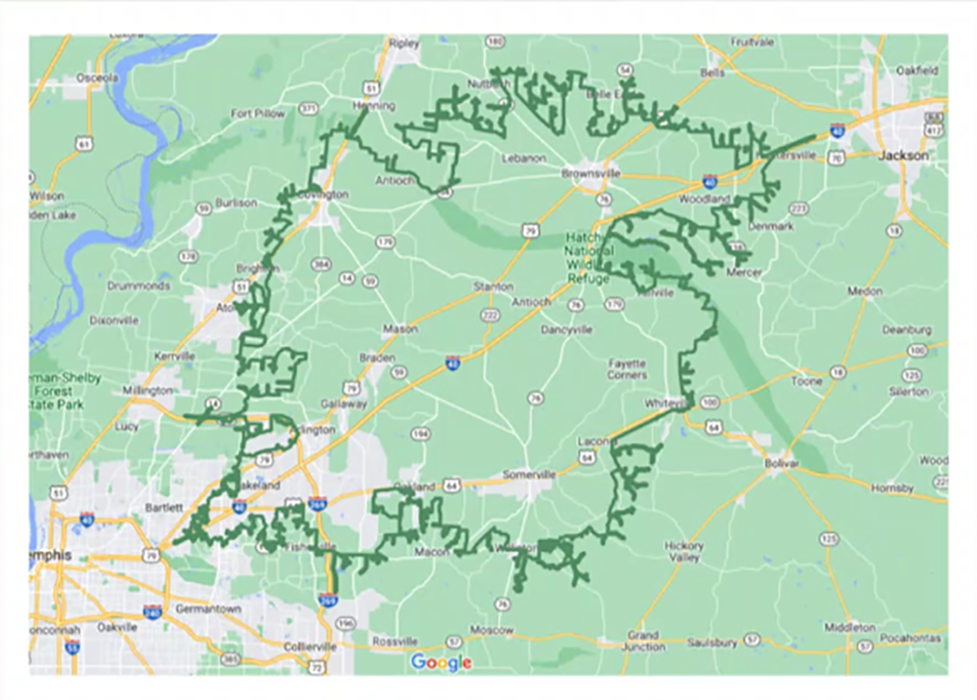

Kanette Keough, executive director of West Tennessee Homebuilders’ Association, said they expect an influx of residents to the area within a 30-minute drive of the Blue Oval facility.

“We understand that nearly a million people live within a 45-minute drive of the Blue Oval site, which is great for Ford. They know they will have a workforce the day they open the doors. People will be willing to make that drive for the higher wages they are paying, but what we also know is that over time, people want to live closer to their job site. The national average people travel to their jobs is 27 minutes. That means a lot of the counties in West Tennessee that have been losing population in the next few decades are going to start to see an increase. The question we all ask, though, is where are these families going to live?”

There are challenges to meeting the need created by the Blue Oval development as well as the housing needs in Tennessee overall. Some of these issues in particular include builder confidence, shrinking markets, increased interest rates, material costs, supply-chain issues, workforce shortages, government regulation, and a lack of infrastructure for building.

"Builder confidence is down since 2022, and that’s the first decline since 2011,” Keough said. “There are a lot of reasons for that. A lot of this is being driven by increase in interest rates and the supply chain issues that have dragged on for more than two years. People will go out to put an estimate on a house. They will have a lighting package that, two years later when those lights finally arrive, the costs may be up 33%.”

One of the reason builder confidence is down is due to the health of the housing market, which is defined by how many buyers can afford to participate in the market. Unhealthy markets have a limited number of buyers who can afford to purchase homes in that area.

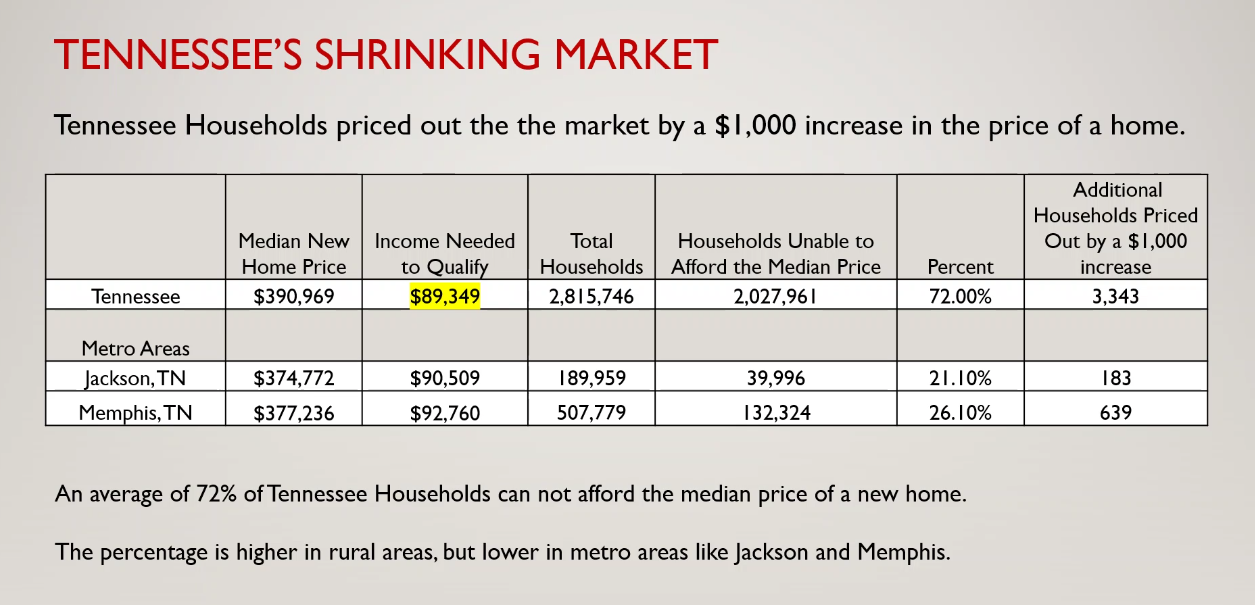

The current median home price in Tennessee is just under $391,000, meaning that the average Tennessean needs to earn $89,349 to qualify to purchase a home. This means approximately 72% of Tennesseans cannot afford to buy a home in the state, and homebuilders are less likely to build homes in rural areas because there is more of a risk associated with that market.

“Builders are much more likely to create that supply if there is that demand,” she said. “The demand shrinks every time more and more people are forced out of the market because of economics. It's really hard to build a house for $390,000 in today’s economy. The figures are a little bit nicer in urban areas like Jackson and Memphis. The reason so many people are building in Memphis and Jackson is because the market is there. If 72% of Tennessean households cannot afford this median-priced house on average, but in Jackson and Memphis that number is closer to 21% and 26%, that means the number of people who cannot afford a home in a rural area is higher.”

Interest rates have created a challenge for many potential buyers with a national average interest rate for mortgages around 7%. The fact that prices of construction materials have also increased 35% since January 2020 mean that homebuilders are facing tighter than ever profit margins to buy materials and provide labor while still producing a product that is not out of the reach of the average American.

“Every time you add $1000 to the price of a home, it knocks 3,343 Tennessee households out of the market for that house,” Keough said. “There are a lot of ways a $1,000 gets added to that price. Most homebuilders in our association have reduced their profit margins to keep building houses. Although some costs have started to level off like lumber, other things are starting to increase. You add to that the time that it takes to get these materials, and time is money. The workforce shortage is scary. You have to realize that about 75% of everyone in our industry is set to retire sometime in the next five years, and for every five people that retire there is only one to replace them. Right now, there is a problem because it’s making it more expensive. Subcontractors can command higher fees for their services.”

Keough said there is more evidence that a healthy mix of different home types builds a healthier community, and that trends indicate more homebuyers want to live in mixed-use communities.

“A lot of it is what price point communities are looking for,” Keough said. “Every time we sit down with someone and ask how they want things to look in their community, they want $2-3 million homes, because they’re thinking about the property tax revenue, but again you have to think about supply and demand. You will see that starter homes are still holding their value. They’re encouraging young families to move into the area and renovate them.”

Doug Swink, CEO of home building and realty company Renaissance Development, agreed stating that “A lot of these modern mixed-used developments have homes that are at a more affordable price point and will also allow your teachers, firefighters, and police officers to be able to live and work there. “

“In a healthy community, not all homes look the same,” said Charles Schneider, CEO of the Home Builders Association of Tennessee. “There needs to be a mix of apartments, a mix of townhomes or single-family attached homes. At some places you will need entry-level subdivisions and, in some areas, you will have more executive housing. All these can be mixed together on one site.”

At present, Keogh said government regulations in Tennessee account for 23.8% of the final price of a new single-family home in the state, which is lower than other states like California but still a concern for homebuilders wanting to make an affordable product and get a return on their investment.

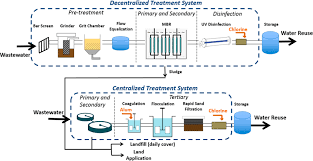

Swink said sewer and water are two of the biggest issues West Tennessee developers face, and many developers are looking at decentralized sewer systems.

“Each community and each development within that community pull together and use these systems to treat their own wastewater,” Swink said. “The technology is there to do this on a small basis so it’s scalable. Instead of having to spend $30-$40 million to build a treatment plant to serve 2 million gallons a day, it allows the community to grow as the community is growing. The best thing is the environmental aspect of it. Since these new technologies are on a smaller scale, it is easier to treat. This technology has been utilized for 40 years in other surrounding states, but it’s newer to Tennessee, who has been very reluctant to accept some of this technology.”

Swink suggested communities may also want to work together to meet coming housing demand. Some communities may be in a situation where they have infrastructure ready for development while others may need to get work to put that infrastructure in place.

By figuring out who is ready for what, communities can direct the initial demand for homeownership into those communities that can easily provide it while other communities build out in preparation for coming waves of demand. Swink also suggested consulting with local developers about how to meet regional needs together.

“We need to focus on those cities that are best suited to accepting that growth instead of spreading resources out and the process taking a longer period. If all the cities are working together, you can look at a 10-year program to determine when and where infrastructure will come into place, what kind of housing is needed, and does that community allow that type of housing. Planning is a big key to this, a and if communities work together with one another, there is a formula we can follow to accept growth responsibly rather than competing with each other.”

To find solutions to housing needs, Keough suggested community leaders sit down with the homebuilders who operate in their area to find out what specific challenges they face and educate themselves on the ways these challenges can be met. The Home Builders Association of Tennessee also has free resources and tool kits available for communities.