Strategic planning for grants essential as project costs soar

By KATE COIL

TT&C Assistant Editor

Many municipalities end up sacrificing valuable projects because they can't navigate the network of state, federal, and private grant funding.

Regardless of size, municipalities can take a strategic approach to grant funding. In this way, they are better able to coordinate upcoming grants, prepare successful applications, and ensure the funding is closed out correctly once it has been received.

During a recent West Tennessee Planning webinar, Brooxie Carlton, assistant commissioner of Rural and Community Development with the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development (ECD), explained how cities can be more strategic when applying for grants.

By adopting this approach, Carlton said she has seen both the state and communities better leverage funds to do more.

WHY PLANNING WORKS

As the cost of capital and other projects rises, many communities must bundle grants to complete projects previously funded by one grant. Phasing projects is another way to stretch grant funds.

“Unfortunately, you can’t come to CDBG for a $500,000 project and max something out,” Carlton said. “It can be hard to figure out how to do CDBG, EDA, and USDA all in one project. Aligning projects with funding priorities, making sure your projects and the funding sources work together takes some planning and moving parts and pieces as well. You may need to pull out some parts of the project and to think about whether phasing out a project makes sense to do.”

Carlton noted many grants now have required planning and due diligence portions with the Delta Regional Authority and the state’s Three Star Program offering grants to cover these costs.

Carlton said that when it comes to securing a local match, budgeting is key. “When you’re preparing your city budget in May, you need to think about a grant application you want to submit next January,” she said. “You also need to make sure there is money for operations and maintenance.”

Strategic planning can also give officials time to improve a grant application by seeking input from the funding entity and finding ways to tie the application to other ongoing opportunities. Carlton said most software can tell the granter when the application was submitted. Those who show they have been consistently improving their application may get more consideration over those who submit it last minute.

BEING PROACTIVE

Carlton said proactively looking at funding program requirements can help develop a winning application. Grantees should consider the application window, when the project needs funding, and if a project can be delayed to fit the application period.

“Some grants take a long time to apply for, but the notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) is only open briefly,” Carlton said. “We have one we filled out for the state where we knew it was coming, so we started working on it early. We figured out what we needed to submit. They opened the NOFO and announced applications were due in a month. We wouldn’t have had the time to complete it on time if we hadn’t been working ahead. You have to start early on a lot of these, especially federal ones.”

Different grants have different timetables, making it useful to keep a calendar of dates like NOFO releases, webinars and forums, application deadlines, and other announcements, like TNECD Department of Rural Development keeps online.

Calendars can also help determine which grants can be bundled together. Carlton suggested signing up for email lists to ensure no opportunities are missed. Participating in forums, webinars, and other informational sessions is also vital.

Reviewing past reference materials about the grant and projects that have successfully earned the grant in the past can provide information to bolster an application, Carlton said.

“If it is not a grant that is open right now, most likely last year’s information is still going to be there for you to look through,” she said. “People like to talk about their wins. You can go to the website, see who got the grant last year, and then call them up to ask about their application, for copies of their application, and they are usually generally open to providing that information. You can ask the grant entity, too, because those are typically public record.”

Grantees should establish a process for effective decision making with boards and commissions and keep them up to date on how the process works so they are ready to do their part when necessary. Communicating with regional, state, and federal agency partners and staff is also a valuable tool to making a strong application, and Carlton said many agencies have staff members whose sole job is to provide aid for grantees. Seeking input from development districts, outside consults, TNECD, and UT-MTAS personnel can be valuable.

THINKING STRATEGICALLY

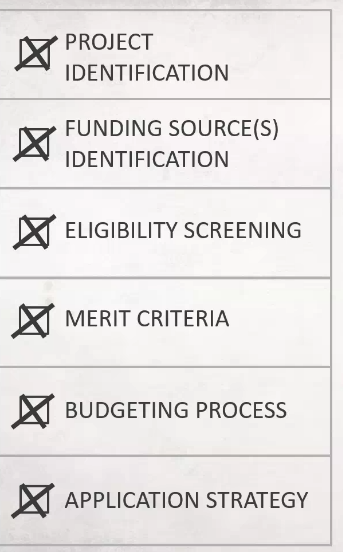

A good strategic plan for grants begins with project identification. Needs should be identified, evaluated, and prioritized before breaking them down into projects based on funding priorities. Carlton said to identify baseline project components, such as the type of project, funding range, timeline, partnership opportunities, and consultants or resources.

The next step is identifying funding sources and their application timelines. Once that is done, grantees should find which projects are most appropriate for funding opportunities and revise project prioritization based on available funding.

Assess if a project is ready for the scope, definition, and purpose of the grant. Applications may require National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and environmental needs; a schedule; an estimated budget; public engagement; and the status of project design, procurement, or contracting. Carlton said NEPA requirements, among others, can take six months to a year to conduct, while some application windows are only a month long.

The third step is an eligibility screening evaluating the project’s alignment with the grant program’s requirements. and determining the lead applicant for partnered projects. At this point, the application should be assessed for competitiveness. A competitive application will include merit criteria of the project; the project’s alignment with state, regional, and local goals. This is also the time to answer any outstanding requirements and refine the application’s strengths.

Strategic grant planning also includes budgeting for upfront costs, local matches, and costs for grant compliance. Surprise financial requirements can sink an application. To ensure municipal budgets are prepared ahead of time, Carlton recommends developing a five-year funding strategy to help with long-term grant feasibility and annually revisiting this plan during the budgeting process.

“The last thing a funder wants to do is fund something you aren’t going to be able to operate and maintain,” Carlton said.

FINAL PHASES

Prior to the NOFO, grantees should adjust the project scope to fit funding criteria; ensure completion of engineering, environmental, and fiscal analyses; and reach out for support statements from state and federal lawmakers.

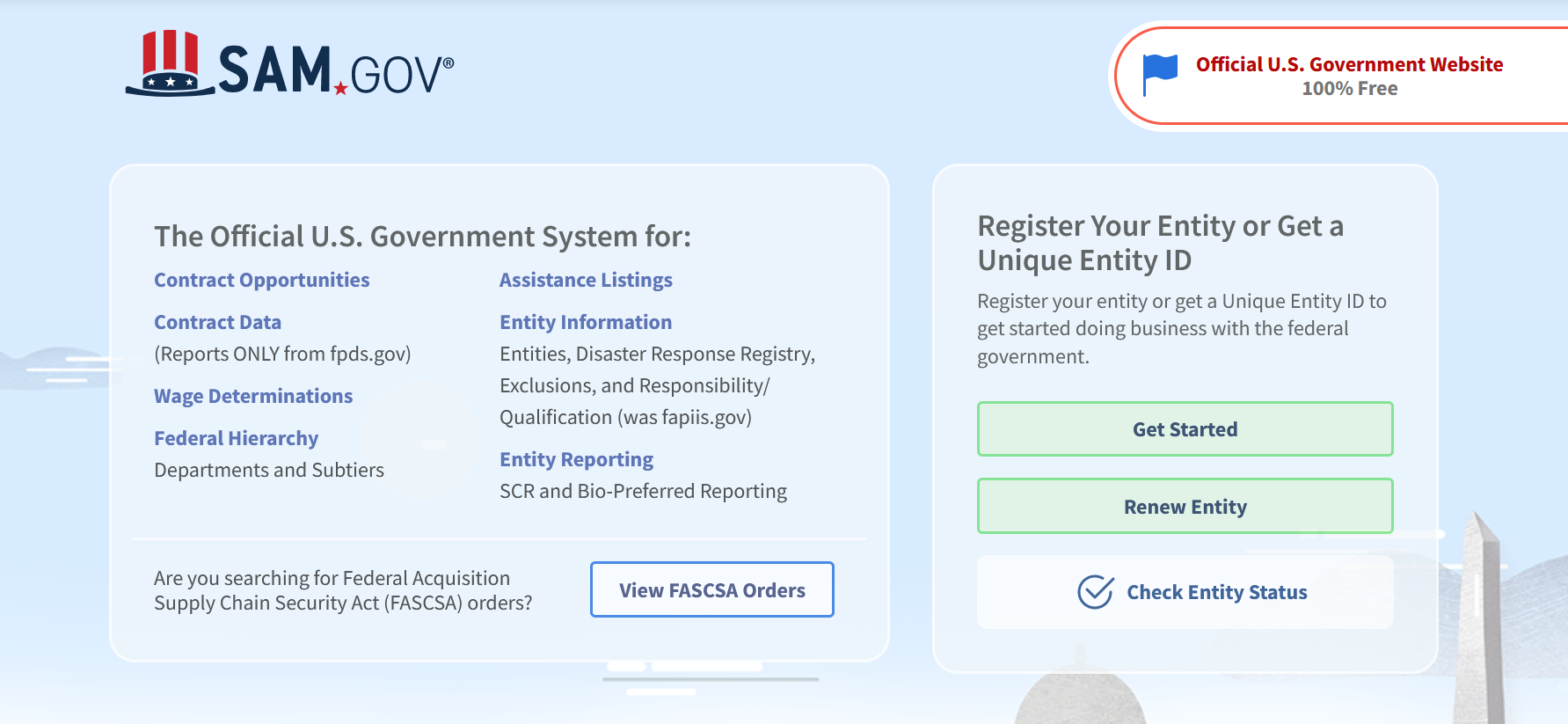

More recently, entities must update their SAM.gov or grants.gov registration. Carlton recommends having more than one point person for this registration and adding its required updates to the strategic grant planning calendar as it is easier to update the registration than redo it.

“That is something we are seeing right now really delay projects,” Carlton said. “They have gotten really tough on SAM registration, and we cannot award a grant with ECD's pass-through of federal money if the entity doesn’t have a SAM registration. If you are using grants.gov to apply, they won’t even let you apply.”

Carlton said to use the time between the NOFO and due date to gather letters of support, write the grant narrative, and adjust the story and graphics to fit requirements. With due diligence done, grantees can easily use language highlighting the grant’s priorities, formulate a clear statement of needs, provide necessary data, and make easy-to-read text, maps, and graphics.

“We always say your application needs to tell a story,” she said. “You can have four different people working on the application and putting in their pieces, but you need one person in charge to make sure it flows and tells a story. Grab the reader the first chance you can and keep them engaged in the application.”

Carlton also advises giving funders everything they ask for but only in the exact pages required.

“Make it easy to read and look good; it may take some extra time, but it’s easy to do,” she said. “No funding source has time to read anything extra. Each question is in there for a reason and needs its own answer, but nothing extra.”

Finally, Carlton said ensure planning has been done for the implementation, output, outcomes, and sustainability of the project alongside the application. This will help with closing out the grant at the end of the process.