Sportswriter Sally Jenkins details life lessons learned from top athletes

BY KATE COIL

TT&C Assistant Editor

From the gridiron to the balance beam to the tennis court, the way superstar athletes prepare for peak performance can be adapted by others to achieve success.

Sally Jenkins presently writes for The Washington Post and previously worked for Sports Illustration, winning the Associated Press Sports Columnist of the Year award five times and becoming the first woman inducted into the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Hall of Fame.

Her new book, The Right Call, explores how the skills these athletes use to stay at the top of their game can be applied to achieve success in work and life. Jenkins discussed these lessons and her experiences in the sports world at TML’s 84th Annual Conference in Knoxville.

DESICION-MAKING

Jenkins said a lot of what athletes do can be related back to working in municipal government.

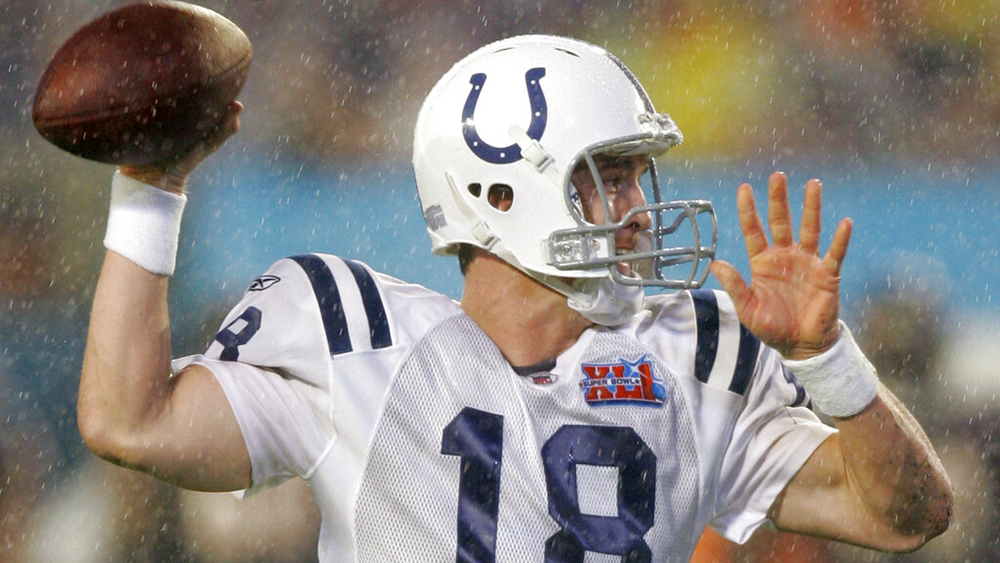

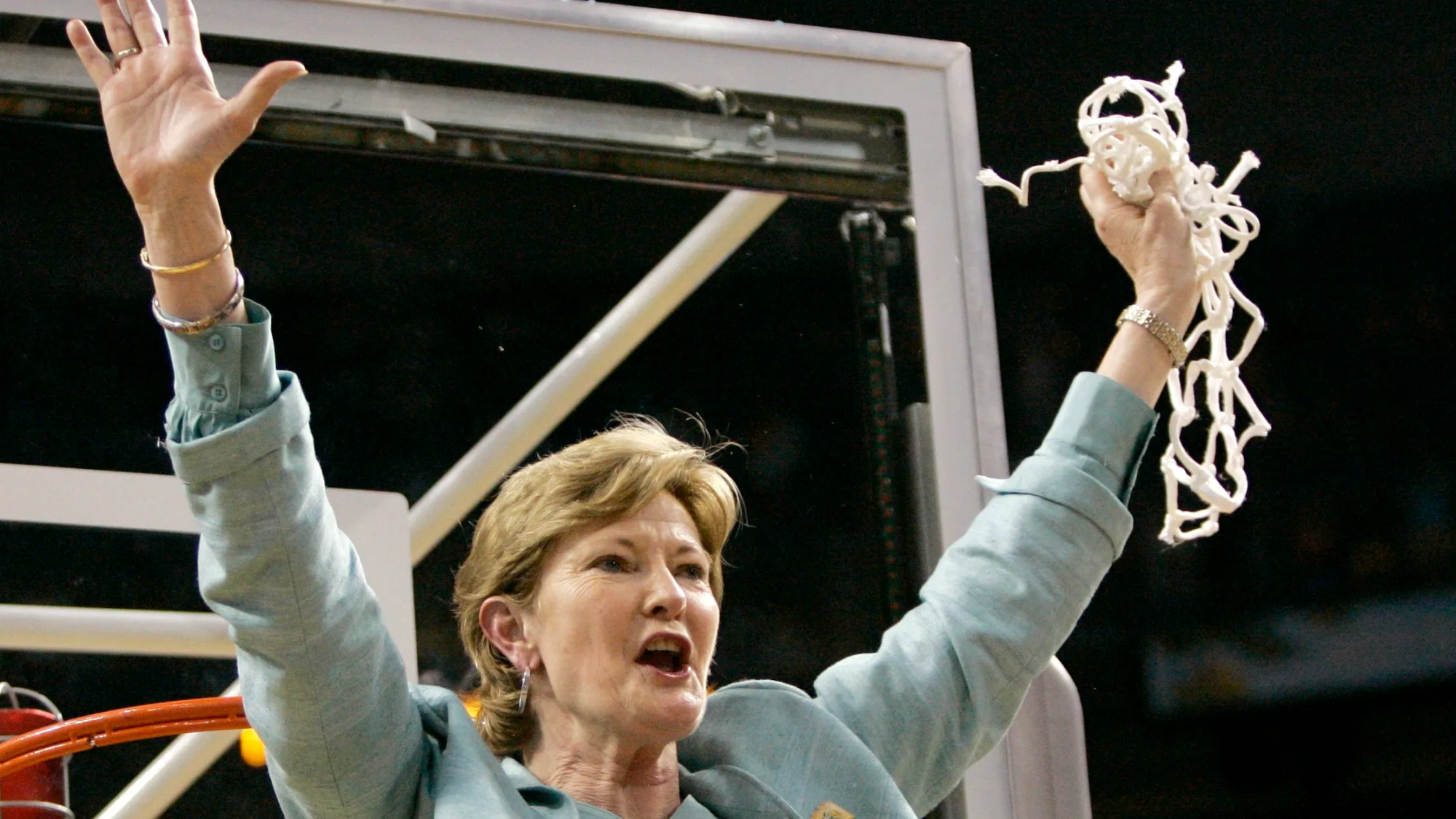

“Thinking about what you all do for a living, the constituencies you have to manage, the people you have to answer to, the organizations that you coordinate with, the pressured situations that you can encounter, I wanted to think about what people like Peyton Manning and Pat Summitt have to offer to you,” Jenkins said. “When I interviewed this cross-section of people for this book, I really wanted to get at what they had to offer me and you. What lessons can we apply?”

Jenkins said sports stars often make many micro-decisions under pressure. She said Simone Biles decided to withdraw from the Tokyo Olympics due to “the twisties” because it could have impaired her decisions in the air, potentially leading to life-threatening consequences.

“Judgments under duress tend to come in the face of multiple stimulus,” Jenkins said. “A lot of times when you’re making decisions, I bet you have a lot of things coming at you all at once. You are trying to sort through them and prioritize them. Pat Summitt told me once, ‘Everyone who walks in my office is walking in with a problem. They’re not walking in there to tell me I did a great job. They are walking in there with something for me to solve, so you better like solving problems if you want to sit in that chair.’ What I have learned is that the people who end up making critical decisions on a consistent basis, follow several key principles that help them make more sound decision making under pressure.

CONDITIONING

The brain will rob muscles of the energy to function, and Jenkins said a Cambridge University study showed how champion rowers performed poorly at physical tasks when their brains were engaged in cognitive tests.

“What goes into your brain and your body comes out in your performance,” Jenkins said. “I don’t care if you’re performing on the balance beam or sitting at a conference table, what you put into your body will come out.”

World champion chess players can burn up to 6,000 calories during a match from mental focus alone, the equivalent of running for an hour-and-a-half on a treadmill. Jenkins said scientists fit chess players with FitBits and heart monitors to see their physical reactions during the game.

“You see guys sitting there perfectly still over a chessboard and their heart rate is going at a 130 beats per minute,” she said. “That is part of what pressure does to us. One of the ways to cope with pressure is conditioning. Caitlin Clark shoots 300 shots a day, and about 2,000 shots a week...It is one of the biggest misapprehensions of the people I cover that they are born possessed of some ungodly or freakish gifts. Scientific American at one point tried to measure Michael Phelps’ anatomy to see if he had some freakish quirk in his body, but it turned out he’s regularly proportioned for a guy who is six-foot-four. One of the scientists said it can’t be that he works his guts out right?”

Jenkins said Phelps swam five miles daily to win a world-record number of Olympic medals, even on holidays and his birthday. As a result, he was in the physical and mental shape he needed to cope with Olympic pressure. When it came time for the most difficult of his races, Jenkins said Phelps’ conditioning allowed him to make last-minute decisions that didn’t compromise his physical performance and helped him win the race.

“Pressure is real; it’s not a state of mind,” Jenkins said. “We tend to think of pressure as a state that is imposed on us or that we impose on ourselves. It’s not. It’s a real physical barrier... When you feel stress, the fight or flight response kicks in. Your body doesn’t know why you’re stressed. Your body is reacting in a very primal way."

Under pressure, the human body reacts by shunting blood from small to large muscle groups, which can cause the loss of fine motor control and tunnel vision. Athletes often make themselves purposefully uncomfortable to train their bodies to cope with pressure.

PRACTICE AND DISCIPLINE

Jenkins said “deliberate practice” is different than conditioning because it is more about making small refinements to weaknesses rather than acclimating the body to pressure.

“Deliberate practice was defined by Erik Erikson, who was trying to answer the question how many hours of practice does it take to become world-class in something,” she said. “That is where you have heard the statistic it takes 10,000 hours of something to be great at something. It’s an interesting statistic, but it’s actually misused. What Erikson was talking about was 10,000 hours of deliberate practice under the eyes of a trainer, coach, or boss correcting minute weaknesses and unconscious incompetencies. Studies have shown even people who consider themselves experts can be ignorant of their deficiencies in about 20% of areas that are critical to areas of their performance.”

Jenkins said deficiencies can even lead experts to make a series of small mistakes that negatively affect their performance. She said Peyton Manning is an example of how to overcome deficiencies through deliberate practice.

During the first three years of his NFL career, Manning led the NFL in interceptions. He began his deliberate practice by watching tape of every interception he had ever thrown and then tapes of all the throws that could have been an interception but weren’t to see what had happened differently.

Manning and his coaches found that under pressure, his footwork went off and it was costing him accuracy and decision-making ability. He then deliberately began practice drills where his feet were put off balance so he could train his body to respond.

Jenkins said the Colts would practice in wet conditions once a week to prepare for games in adverse weather, leading to the Colts winning the 2007 Super Bowl in rainy Miami. Jenkins said mimicking the conditions in which the performance will take place can mitigate the impact of pressure.

CULTURE AND CANDOR

Jenkins said athletes known for performing solo are still members of a team of coaches and trainers, and all teams require a positive culture to thrive.

“Culture is a misunderstood word,” she said. “No strategic decision-making, no matter how smart you are, can work in a culture that is dysfunctional for the simple reason that culture is environment. If your environment is full of clutter, junk, or unhappiness, it can sabotage a really big decision. The Harvard Business Review reported as much as 50% of the competitive difference between companies in the same industry is attributed to culture.”

If a leader is mistrusted by those below them, the decisions made by that leader will also be mistrusted. She said success often comes from having trust in the lower ranks with disillusionment spreading as quickly as optimism.

“One of the distinctions I noticed in Peyton Manning, Pat Summitt, and other great ones in a room is that they never present a problem without also presenting a solution,” she said. “Pat would run tape of the Lady Vols making mistakes, but then would run a second tape of them doing it right. They always walked out of the room feeling uplifted. It’s incredibly simple, but a powerful distinction. So many leaders present the problem without adding the solution at the end of the sentence.”

RESILIENCE AND INTENTION

While failure is inevitable, Jenkins said it is an essential part of the formula to success. She said Summitt is often remembered for her eight championships, not the 30 other years she didn’t win.

“The portion of success is really low for these people,” she said. “Winning is not what they do best; responding to losing is what they do best. Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic over the course of their careers have only one 54% of the points they ever played. The only thing that differentiates them – the all-time No. 1’s - from the middle-of-the-pack guys is a 3-4% difference. That difference is the way they respond to losing a point and come back to play the next once. Pat told me one time a lot of people are afraid to succeed, to go all-in, and say that’s all I can do.”

Jenkins said those who keep at it often succeed

“We all face failure daily,” she said. “We have more than failure; we face uncertainty. We face all these novel problems different from the day before, but we show up. We are showing that flexibility these great athletes show. Showing up is a decision in itself. The more explicitly we can spell out these choices, the less likely we will be bowled by events.”