Tennessee cities still welcoming visitors rollin’ on the river

By KATE COIL

TML Communications Specialist

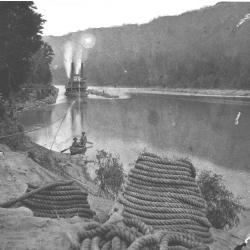

It may seem 200 years out of place to see paddlewheel boats making their way up and down the Cumberland, Mississippi, and Tennessee rivers, but there are still cities across the state where visitors can experience Tennessee the same way many of the state’s early tourists once did.

Paddlewheel river tours are operated in all of the state’s big four cities with Chattanooga’s Southern Belle, Knoxville’s Star of Knoxville, Nashville’s General Jackson, and a variety of paddle-powered boats operating along the Mississippi in Memphis. Those who want to get off-the-beaten path can also opt to take some of the longer cruises that dock in some of Tennessee’s smaller communities.

Clarksville is the starting and ending point for numerous voyages up the Cumberland and to the Mississippi along routes headed to Memphis and Chattanooga in Tennessee as well as Cape Girardeau, Mo., Paducah, Ky., and Florence and Decatur, Ala.

Visit Clarksville Executive Director Theresa Harrington said the summer season has meant literal boatloads of visitors stepping off the dock at Clarksville’s McGregor Park and Cumberland Riverwalk for more than 20 years.

“They come and some bring buses to take them on tours,” Harrington said. “They are downtown when they dock, so some just let them go to downtown and shop, visit the museum, and other attractions. They may bus them out to Historic Collinsville to spend a few hours out there seeing the historical sites. They may also do a downtown hop-on-hop-off driving tour. There is another set of tours where they go to Old Glory Distillery and Beechaven Winery. Each boat has a different itinerary.”

A single boat can bring anywhere from 95 to 150 people into town between the spring and fall. Some cruises have themes, like Civil War history or booze cruises, while others coincide with major holidays like the Fourth of July or Christmas. With three separate boats often docking between 12 and 15 times per season in Clarksville, the boats can easily bring in thousands of tourists.

“We get a lot of people who might not necessarily drive out of their way to go to Clarksville,” Harrington said. “We aren’t a destination like Nashville, but once they come here on the boats, they find they can’t see our entire community in the one or two days they are here. We find a lot of people are coming back. They want to experience the things they didn’t have time to do.”

Further down the Cumberland River, Dover is either one of the first or last stops on the river for boats coming from cruising both the Tennessee and Ohio rivers. Dover’s location near the Fort Donelson National Battlefield and Land Between the Lakes makes it a popular stopover for paddleboat tours, according to Town Manager Charles Parks.

“We have several stops here for the American Duchess and Countess, and they added more boats on this year,” Parks said. “They stop here on a routine basis, and this year we have about 20 scheduled. They stop at the Dover Landing Boat Ramp, and they have buses that take them to Fort Donelson and other tourist stops in town. Fort Donelson has guides who give them a history of the area. They shop and spend a day here before going on. Sometimes they stop back here on their way back.”

Dover Mayor Lesa Fitzhugh said the ships docking in Dover are a highlight for both local citizens and passengers. Fitzhugh said she has built personal relationships with many passengers and crew members.

“I have had dinner and lunch with them,” she said. “I have toured the boats. One time they called and said they would be in Dover the day of the Christmas parade, and the boat’s captain had always wanted to be in a Christmas parade. We arranged for him to be on the Santa float. People from Canada, Vermont, and New Orleans have come here. I stay in touch with a couple I met from Florida. It’s a very personal experience, and we feel very blessed that they want to stop here, and that they continue to stop here. We know when the boats are coming in because you see the posts go up on Facebook with pictures saying ‘the boat’s here.’”

Many of those who have enjoyed Dover’s hospitality on the boat make plans to return to the community.

“It opens the door for the town of Dover and Stewart County as a whole to invite people to come back and visit or even buy property here,” Parks said. “Some of our locals also get on and ride, too. It’s a great experience to see these huge paddleboats coming in. It’s an awesome sight. You don’t realize how big they really are, and when you go on them, it feels like you’re walking into a museum.”

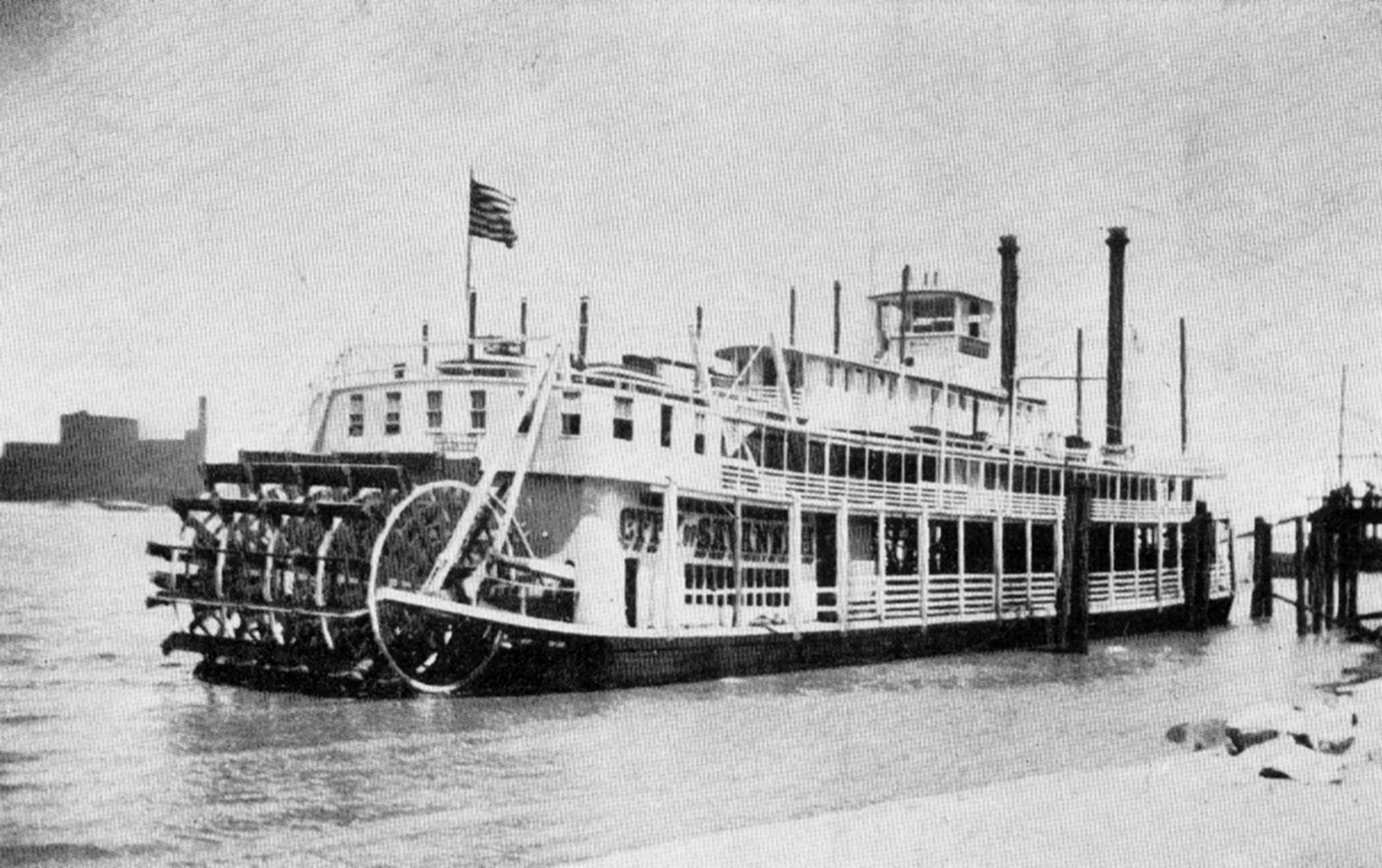

Another one of the usual stops en route on the Tennessee River is Savannah, a city whose history is so entwined with steamships one has been incorporated into the municipal logo. Savannah City Manager Garry Welch said the city has been a stop-off for modern paddleboat travelers for the past decade with another river cruise line planning to add stops in the city in the coming year. The boats typically dock at Savannah’s Wayne Jerrolds Park to great fanfare.

“They have the big walkway they drop down,” Welch said. “We usually have a bluegrass band playing when they come off the boats and the whole time that they’re docked. Most are here for just a day or dock the night before and spend the night. It’s a big deal when they dock, and people often stop to come see the steamboat. A lot of traffic comes into the park of people just taking pictures and seeing the size of some of these boats.”

Welch said visitors to Savannah come from all over America on the tours to take in local sites and history.

“We are only seven miles from the Shiloh National Military Park, so often the cruise line brings in buses and takes historic tours of Shiloh,” Welch said. “There are also one or two buses that tours Savannah’s historic area. We try to cater to the folks who come in off the boats. The visitors often come and spend time at our shopping district. Mayor Robert Shutt has a beautiful home in Savannah’s historic district and often opens up his home for tours and to talk and visit.”

Savannah is also home to the Tennessee River Museum whose exhibits focus on the Tennessee River specifically but also highlight how rivers throughout the state were important to early commerce, agriculture, and transportation.

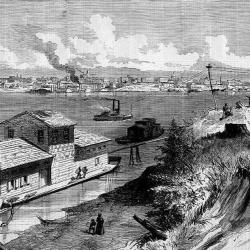

The age of the steamboat officially began in Tennessee in 1811 when Nicholas J. Roosevelt successfully sailed a wood-fired steam craft the New Orleans past the four dangerous Chickasaw Bluffs on the Tennessee side of the Mississippi between what is now the Lower Hatchie Wildlife Refuge and the city of Memphis. Roosevelt was then able to successfully continue on New Orleans, meaning that the Mississippi was now safe to travel its length from what would become Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico.

Soon, steamboats were cropping up all over Tennessee and steamboat travel and commerce led to natural river landings becoming major cities and towns. By 1819, the original General Jackson was steaming the Cumberland with its base in Nashville while the Rocket made its first voyage on the Tennessee River into Alabama in 1822. In 1828, the difficult Muscle Shoals were finally navigated when the Atlas became the first boat to travel the length of the Tennessee River, opening up steamboat travel even further.

Supplies coming in and those being shipped out meant that many communities depending on steamboats economically from the 1820s into the 1860s. Passenger travel also brought new settlers and some of the state’s first tourists. Well before Clarksville’s train depot was immortalized in song, river travel helped make the city into what it is today.

“The river, in our mind, is our other interstate,” Harrington said. “We still have barges going up and down the river, and these riverboats can reintroduce people to that. Clarksville started as a tobacco community and transporting tobacco out on the river. The river traffic played a huge role in our economy and how our county was formed.”

Likewise, steamboats remained a vital link between smaller communities like Savannah and the wider world.

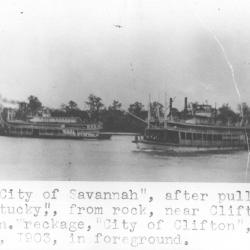

“The first bridge on the river in Savannah wasn’t built until the 1930s,” Welch said. “Prior to that, we had an area where steamboats stopped and were a lot of supplies, especially hardware, was delivered by boat. On the other side of the river from the city is a lot of flat farm land where cotton and grain are raised. Those were taken out on the boats. There were also livestock boats on the river and people would literally drive their livestock onto a boat to take it up and down the river. It was large enough that there was a steamboat named the City of Savannah that worked the river up to the Ohio. We were a very well-known stop on the river.”

The age of the steamboat is generally seen as ending during the Civil War when many of the boats were repurposed as military ships. Harrington said a lot of the history surrounding steamboat travel coincides with local Civil War history.

“We have Fort Defiance up on the hill overlooking McGregor Park,” she said. “A lot of the people on these boats are Northerners who haven’t experienced Tennessee or the South. There are a lot of things you don’t know unless you come and experience the history of these areas.”

Dover was founded around a logging yard adjacent to the river for easy transport, but soon became more known for the battle at Fort Donelson. Fitzhugh said the importance of river travel can be seen in how period forts were built.

“All of the battlefield at Fort Donelson was located along the river,” she said. “If you tour the fort, you will see the cannons there were all facing the river. When you’re on the boat, you are on the same spot where the boats were during the war.”

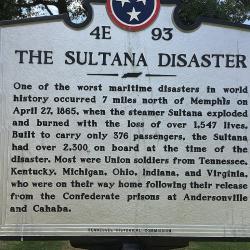

However, it was after the war that perhaps the most famous steamboat disaster in American history happened just outside of Memphis. Carrying a crew of wounded, former prisoners of war from Louisiana, the Sultana was overloaded on its trip up the river and its boilers blew up, killing more than 1,500 – including some 400 soldiers from East Tennessee. Monuments to this disaster still exist in at the Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery in Knoxville and at the Memphis National and Elmwood cemeteries in Memphis where victims are buried. The Sultana remained one of the most well-known and deadliest U.S. maritime disasters until the sinking of the Titanic.

Steamers were still active on some Tennessee rivers despite the rise of the railroad. Carthage, Gainesboro, and Celina still had limited steamboat commerce into the 1920s. It would be the locks and dams created by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Tennessee Valley Authority that put an end to the steamboat industry.

Something then changed in the 1970s with the return of pleasure paddlewheelers to rivers across Tennessee. Ships like the new General Jackson and Memphis Queen began offering nostalgia tours of local rivers. Soon, longer cruises were being scheduled along these old, familiar routes bringing visitors back not just to major riverports but also to smaller towns. Today, modern paddleboats provide a unique experience for travelers.

“If you don’t come in via the river, you miss that whole experience,” Harrington said. “If you aren’t on the river, you aren’t learning the history from that side. There is a whole different type of feel and how you experience Clarksville as a whole.”

Fitzhugh visitors coming in by boat get a chance to see wildlife and history that others don’t get to see.

“It is a totally different experience,” she said. “There is a calmness, and you get to see wildlife. You aren’t stuck in an ocean with nothing around you. You can see wildlife, like our bald eagles, birds, and deer. I also know as I’ve gotten older I realized our history and heritage is so important.”

Welch said he wouldn’t mind taking his own cruise on the river from Savannah

“You can tell when dock and undock, and take off down the river how peaceful it is,” he said. “You’re in nature gently rolling along. When the weather is pretty, you can get out on the deck and see nature at its best. We feel very blessed that we are the in-between stop and that most of them like us well enough to dock here.”