Federal policy changes may shift future of Tennessee's economy

By KATE COIL

TT&C Assistant Editor

Tennesseans can expect changes in both the state and national economy as federal policy shifts bring more economic uncertainty.

Marianne Wanamaker, dean of the University of Tennessee’s Baker School of Public Policy and Public Affairs and a professor of economics and public policy, said Tennessee's economic growth has outpaced nationwide growth over the past 20 years. Tennessee’s economy is 52% bigger today than it was in 2005, and for the past five years, the state’s growth has exceeded 5% per year.

“You may get growth from having more workers, from the size of the workforce increasing,” Wanamaker said. “The other way you get growth is if the people in your workforce get more productive; they produce more stuff. Economic growth is the sum of those two things. Tennessee’s economy is growing both because the workforce is growing and so is production. That seems like a very simple statement, but it’s not true in every state.”

POPULATION GROWTH

Tennessee’s population growth has exceeded the national average, with the state averaging 1% per year growth over the past 20 years while the U.S. as a whole has only seen a third of that growth. Tennessee is the 11th fastest-growing state in the nation.

However, the state ranks 33rd in terms of natural population growth, meaning that the state birthrate doesn’t outpace the number of deaths. Tennessee is also 39th for international migration. Wanamaker said people from other states moving to Tennessee are driving the population increase, with Tennessee ranking 7th out of all the states in domestic migration.

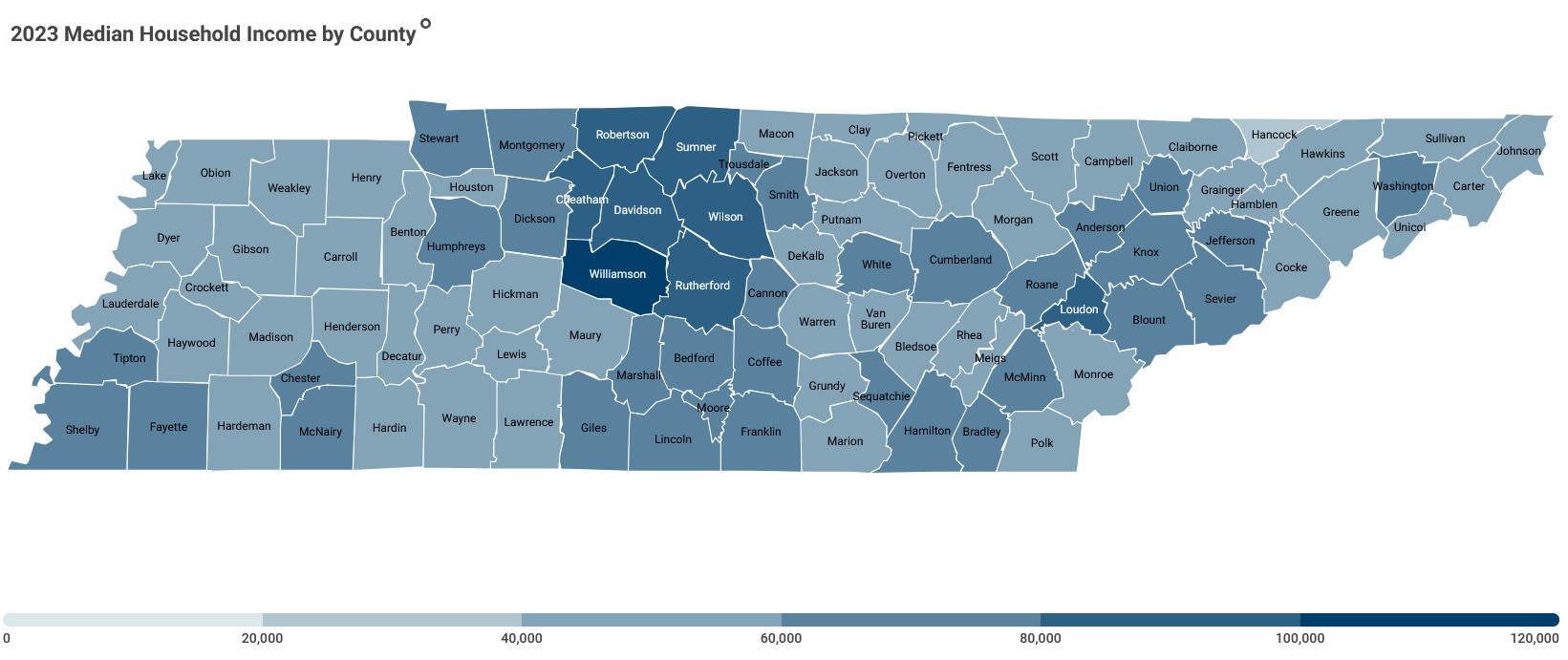

Prior to 2020, most of the domestic migration was concentrated in Middle Tennessee, but Wanamaker said it is spreading to East Tennessee and more rural areas of the state. She expects the trend to also reach West Tennessee.

And Wanamaker adds that we can anticipate some changes to the makeup of those moving in.

“Although we are not highly ranked in terms of international migration, that segment has become an increasingly important part of our population growth running up to 2025,” she said. “Between 2001 and 2010, we got roughly 90% of our population growth from both domestic and international migration with that number split pretty evenly down the middle. Between 2022 and 2024, international migration became a much more significant factor in our population story.”

Heading into 2024, international migration to the U.S. - both legal and illegal – represented 84% of U.S. growth.

“Remember, if we close the borders, this country grows by 0.1% per year,” Wanamaker said. “Almost all of Tennessee’s population growth came from international migration in 2024, comprising three-eighths of new state residents. We won’t know until the middle of 2026 what the 2025 numbers look like, but I can guarantee you they will be different because we have shut off the international migration valve for the most part, and especially the illegal immigration part. That was particularly impactful for Tennessee.”

While the majority of those moving to Tennessee prior to 2024 were from within the U.S., the paradigm was beginning to shift to include more international migrants to the state. Wanamaker said policies of the current federal administration have largely reversed that shift.

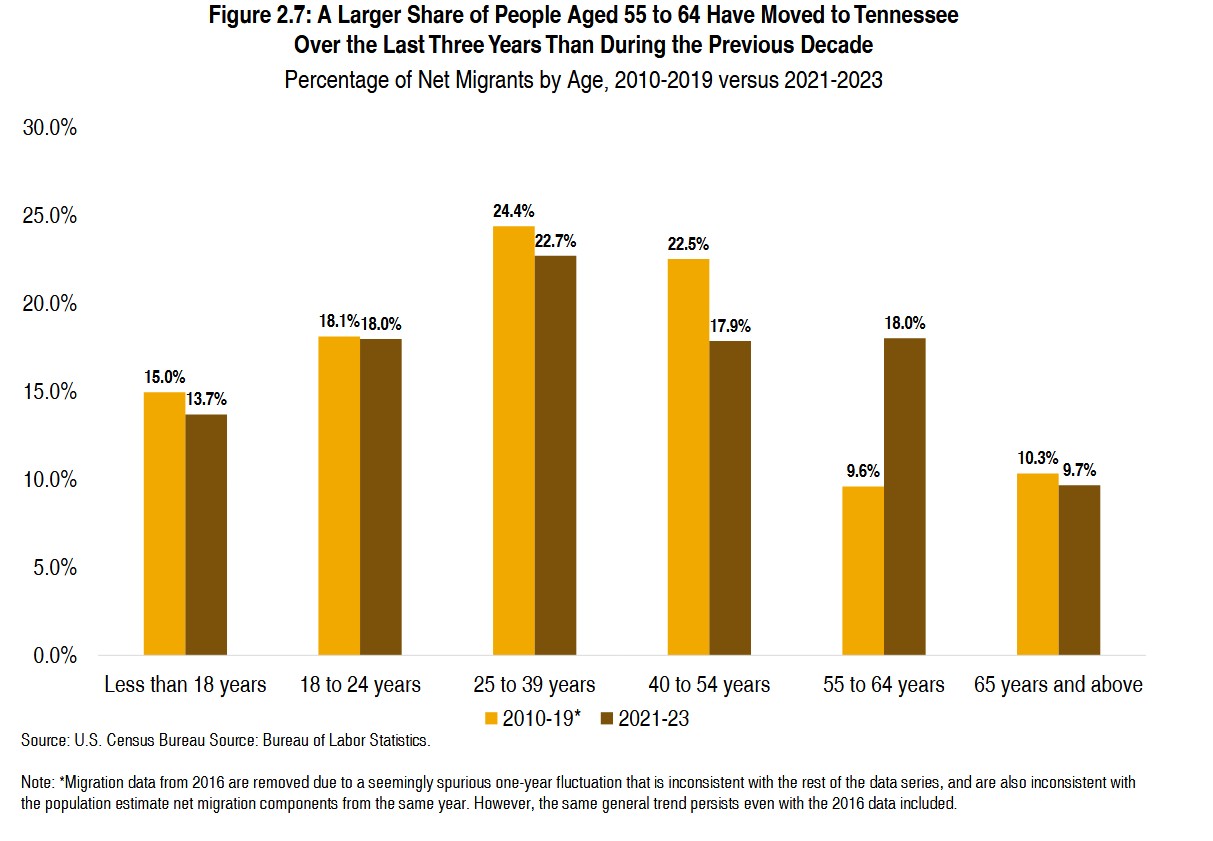

Wanamaker said there is a perception that the majority of new migrants to Tennessee are retirement age and not contributing to the workforce. Between 2021 and 2023, two-thirds of new residents were under 55. While the number of seniors is increasing, Wanamaker pointed out they pay property taxes and tend to spend money locally but don’t have students enrolled in local schools.

There is also a misconception that many working-age individuals coming into the state have a remote job elsewhere. Wanamaker said even those with remote jobs are still integrated into Tennessee’s economy.

LABOR PRODUCTIVITY

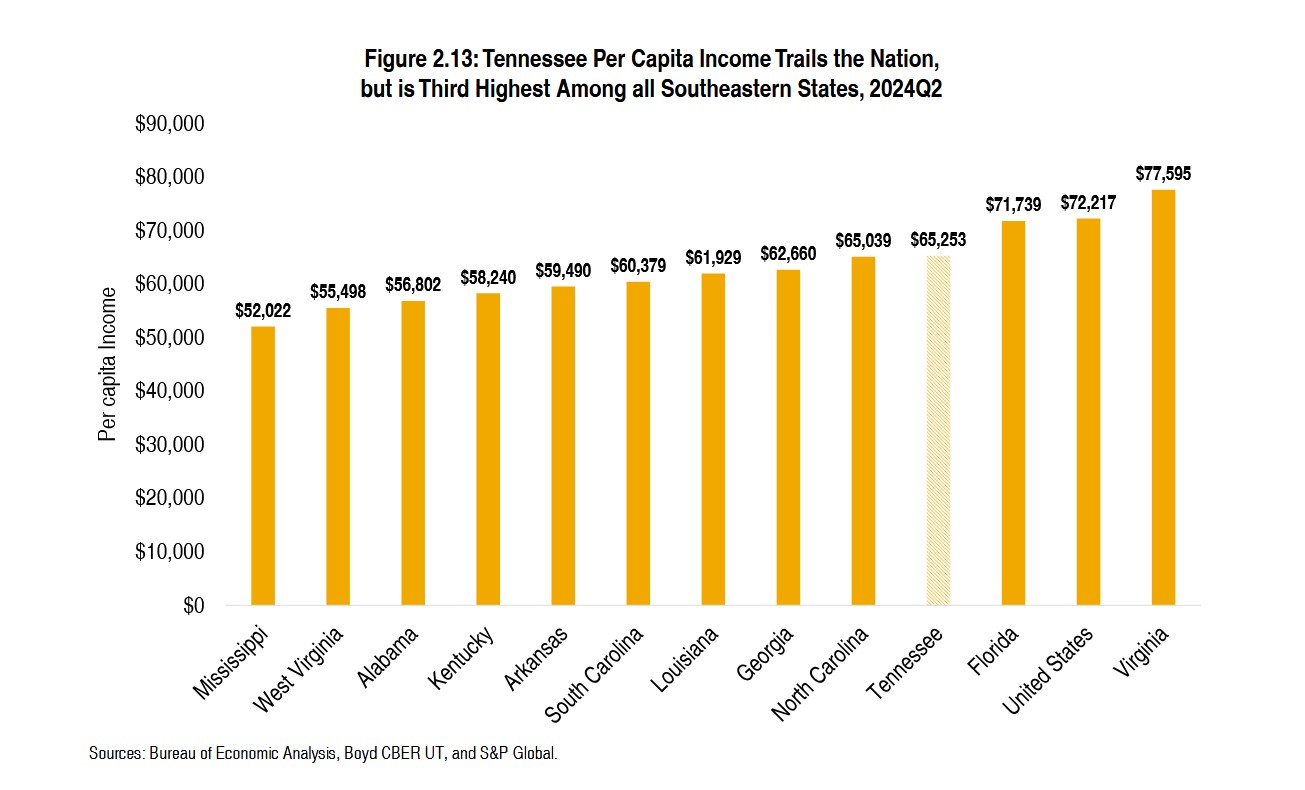

One way of measuring labor productivity is per capita income. Tennessee is about 10% below the national average when it comes to income per capita. While income has grown somewhat compared to other states in the southern U.S., Tennessee has not seen much change since 1995.

“We’ve done a great job within the South. We have outperformed what you might have expected if you began tracking this in 1995, but we haven’t changed our relative position within the U.S. overall in that time period. We started the time period at 90% of the U.S. average, and we ended at 90%. That doesn’t mean we didn’t grow; we did. We kept up with the rest of the U.S., which is a win. There are some states that did not do that.”

However, the state has not made progress in terms of labor productivity.

“If you look at the industry mix in the state of Tennessee, we don’t look different from the rest of the country,” Wanamaker said. “So that’s not it. What is true is that within each of those industries, Tennessee tends to have lower-paying jobs. What we want is a situation where we recruit the Googles or the Oracles to come to Tennessee, and we want the jobs they offer Tennesseans to step it up a notch. We want it to reflect the U.S. average.”

To do that, Tennessee has to show these companies they have the workforce to meet that demand. At present, Wanamaker said the state ranks 47th in the number of students obtaining science and engineering degrees.

“We have to be at the forefront of stuff,” Wanamaker said. “As things are happening, as tech is expanding, and as science is becoming a bigger part of our lives – which it will – we have to be prepared for that. If you look at seventh grade test scores in math and science, we’re fine. We are above the national average. It is what happens after that in that 15-24 age group. It’s something all of us as Tennesseans are going to have to work on. We are going to have to prepare that next generation for whatever that new economy is. It isn’t as simple as making them all major in STEM.”

BIG PICTURE

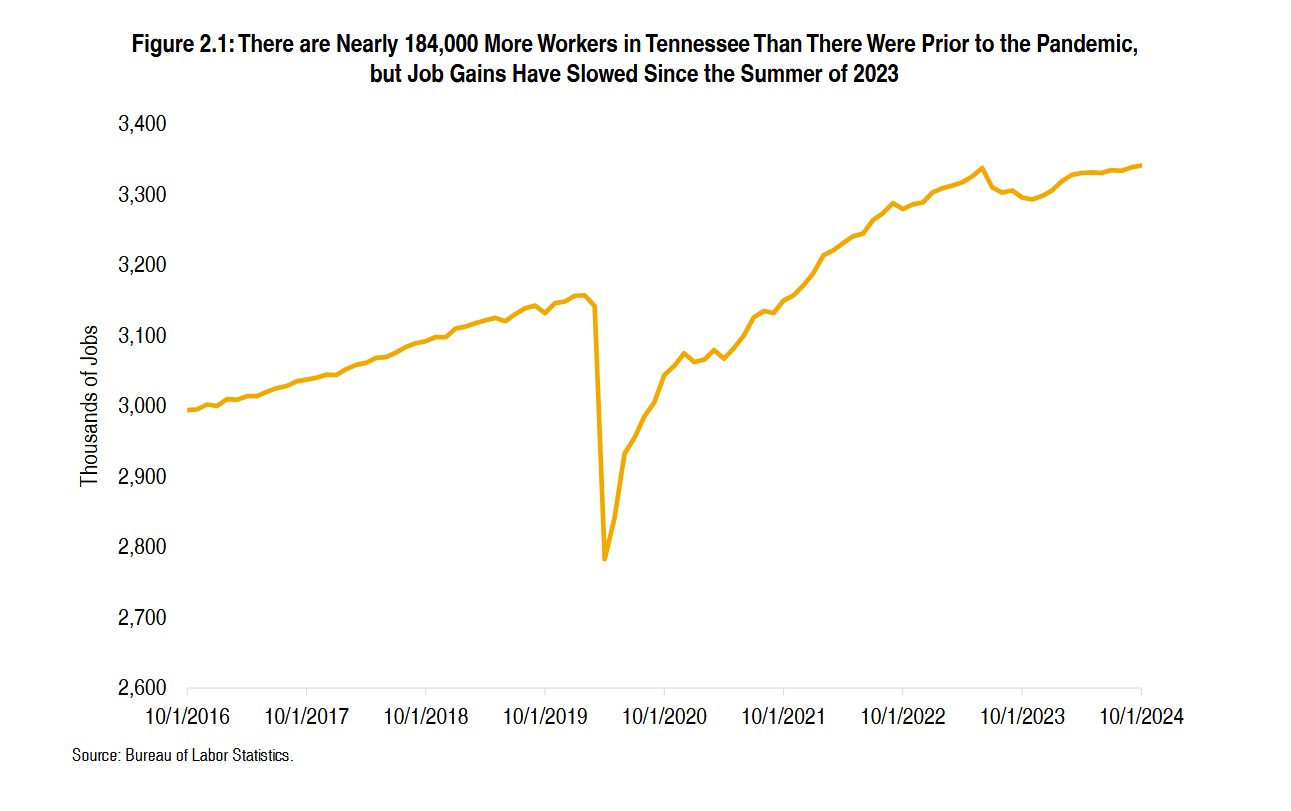

Despite Tennessee’s positive trajectory, Wanamaker said what unfolds on the national level ultimately affects what happens in the state. The recent federal reports showcasing flat job growth in the country on average between May and July is one indication of where the federal economy is headed.

“The Trump administration – as they said they would – has substantially reduced in-bound migration to the U.S., both legal and illegal,” she said. “People aren’t enthusiastic about coming right now, and they made it super hard. On our own, we are only growing by 0.3% per year, so if you think about it, that’s how much workforce we can add annually. Your workforce doesn’t grow much faster than your population. We really have kind of kneecapped ourselves in terms of the number of workers entering the market.”

Meanwhile, industrial policy, including trade and tariffs, remains a moving target, which Wanamaker said can make business investment difficult.

“This is a transition period; whatever we are headed toward, we aren’t there yet,” she said. “The road is going to be rough with low job numbers and higher unemployment numbers. Wherever we get, Tennessee stands to benefit if – in fact – there is a resurgence in manufacturing.”

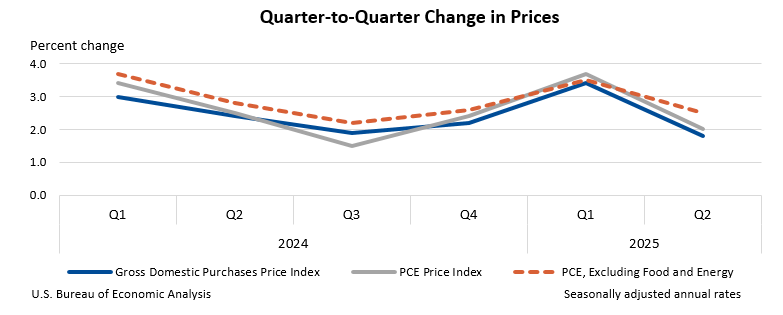

Wanamaker noted that the “Big Beautiful Bill” lacks mechanisms for improving the economy as the economy wasn’t its major focus. The bill doesn’t include changes that would impact the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), the economic measure of the total market value of all goods and services the country produces. The goal of the bill was a continuation of the tax code, which can prevent a downturn but doesn’t necessarily fuel an upturn.

“When the government takes in more revenue and spends less money, that’s a fiscal contraction,” she said. “That is the opposite of what we do in a recession. In a recession, the government spends money. In this moment, the Trump administration is choosing fiscal contraction, to spend less money. You take that amount they have contracted and spread it out over a full year, it’s 2% of the GDP.”